Be better informed about the litigation process.

This free e-book, What Nonprofit Managers Need To Know About Lawsuits, is designed to help nonprofit managers, board members, and nonprofit staff to be better informed about the litigation process, so that they can work more effectively to manage lawsuits lodged against them.

Table of contents.

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Getting the facts: That key first step.

- Chapter 2: Lawsuit basics: When, what, where, and how.

- Chapter 3: Yikes! I’ve been served with a lawsuit!

- Chapter 4: What are the steps in the lawsuit process?

- Chapter 5: Conclusion.

- Appendix A: Glossary.

- Appendix B: Member resources.

Please note: This e-book is designed to provide general information about responding to lawsuits based on our many years of experience in handling claims and lawsuits against nonprofit organizations. This e-book is not intended to offer legal advice or counsel. The information contained in this e-book does not alter the terms of any insurance contract or the law of the jurisdiction which is the site of any potential claim or suit. The terms and provisions of your insurance contract provide the scope of the applicable coverage. Because the areas of law constantly change, nonprofits using this e-book should not rely on it as a substitute for independent research.

Introduction:

The most common reaction to being served with a civil lawsuit is shock, denial, and disbelief. Whether or not your organization is ultimately found to be at fault, the lawsuit process can be a frightening experience. Part of the anxiety stems from not understanding the process, the vocabulary, and what is expected of you.

This e-book is designed to inform nonprofit managers, board members and staff about the litigation process, so they can work more effectively with us to manage lawsuits lodged against them. The e-book begins with information about how to properly document incidents that may lead to lawsuits and then takes the reader step by step through the legal process generated by a lawsuit.

But first, we need a note of clarification. Throughout the e-book we use the word “insurer” to mean the company that takes in premium dollars and pays out money to defend and settle claims. Whatever the form of the “insurer,” the word is used interchangeably with us. However, in some cases where we express our company philosophy or refer to a service we offer that other “insurers” do not, we use ”Nonprofits Insurance Alliance” or “NIA” instead of the more generic “insurer.”

Also, references to “your attorney” mean an attorney hired by your insurer to represent you and/or your organization in a lawsuit. In all cases we have referred to the individual who places coverage with an “insurer,” the intermediary, as the “insurance broker.” Some folks may also refer to that person as their “insurance agent.”

Chapter 1: Getting the facts: That key first step.

A client has just tripped over a chair and fallen down at your luncheon program for low income families. He says he is fine and just needs a ride home. What is the likelihood this will lead to a lawsuit? What should you do to protect your agency?

Also consider this: One of your employees returned from a business errand in the organization’s van. The employee told you he was involved in a minor collision. He tapped the rear end of another car at an intersection, but there was no damage and no one was hurt. The police were not called, but your employee exchanged insurance information with the other driver. Now it is almost a year later and your organization is served with a lawsuit for damage to a vehicle and injuries claimed by the driver and three passengers. You have no recollection or record of the incident. The driver named in the lawsuit no longer works for you.

Sound far-fetched? At Nonprofits Insurance Alliance, we receive at least one of these lawsuits a month. Without pictures of the cars and statements from the drivers, we are in the position of trying to prove the injured parties are exaggerating their claims without the tools we need to do so. How can you make sure this doesn’t happen in your organization?

Even with the best risk management, incidents occur at nonprofit organizations. Many of these are beyond anyone’s control. Often it is the inattention of the individual involved that results in these injuries. However, sometimes these injuries are caused by unsafe conditions or inadequate supervision at the nonprofit. Sometimes it is a combination of several factors.

What should I do?

Whatever the cause, when an incident occurs at your nonprofit, you need to take a few steps to protect your agency. In our previous examples, the folks may go home, have a warm cup of tea and feel perfectly fine. However, that is only one possible outcome. It is at least as likely these individuals could experience pain on waking the next day and, after further investigation by a physician, discover a pulled muscle, a cracked bone or some other injury. They could also connect with an unethical medical provider or attorney and concoct soft-tissue injuries that may not truly exist. You should be prepared for a claim for damages, or possibly a lawsuit.

Foremost, when an incident happens, make sure that emergency personnel are called . If emergency care is not warranted or desired, make sure the person or persons involved in the incident, however minor, have ample time to rest and collect themselves before they go about their business or leave your premises. Keep the name and phone number of the individual. If possible, you may even want to call that person in a day to see whether he or she is truly feeling well. As litigious as our society is, we still find that a little common courtesy and concern go a long way.

Once the individual has been taken care of, it is time to take care of your agency. That means briefly documenting the incident and reporting it to your insurance broker in case a claim for damages is made.

What should I document?

- Record the name, address and phone number of all persons involved in the incident, as well as the date of occurrence.

- Express concern for the individual, but do not promise to pay any damages. It is premature to determine who should pay before the incident is investigated.

- Make a list of witnesses to the incident, including names, addresses, and, most importantly, telephone numbers.

- Write a brief description of the incident and note the condition of the area at the time of the incident. (You may wish to use the Incident Report Form in Appendix B.) Be sure to note the time of day, lighting in the area, any foreign objects, etc. In cases of slip and falls, it is important to note the type of footwear the person was wearing and the condition of the floor at the time of the incident.

- Take snapshots of the area, if possible. An inexpensive camera or a cell phone camera can be a big help in these cases. If surveillance video has been taken, save that portion of the video and note the date and time it was taken.

- Keep this information on file and send a copy of the incident report to your insurance broker.

All this record keeping may seem like an excessive interruption in your busy day. However, good notes on incidents like these taken right after the incident have proven valuable in defending cases against our nonprofit members. Concise, accurate documentation can provide a powerful defense.

To assist our members, we provide an Incident Report form at the front of the insurance policy. We also have this form available on our secure member portal.

Reporting the incident.

At Nonprofits Insurance Alliance, we believe it is important for you to report all incidents to your insurance broker, who is expected to forward the information to your insurer. Besides the information you send, your broker will complete an ACORD form which is a standardized form required by insurers. Not all insurers want to have all incidents reported to them. Sometimes, they want to know about the incident only if a claim for damages has been presented. We prefer to have the information about all incidents, whether or not there exists a claim for damages, so we can determine whether an investigation is warranted. We suggest that you report all incidents to your insurance broker and let him or her determine whether to forward it to the insurer.

Most incidents will not result in lawsuits. However, many will cause a claim for damages. If you have reported an incident to your insurance broker, an insurance adjuster will probably call to ask you details about the claim. Depending on the facts and the seriousness of the claim, an insurance adjuster may make an appointment to meet with you and your staff at length. You should cooperate with the insurance adjuster’s request for information to the fullest extent possible.

Sometimes an unscrupulous attorney will call and fail to tell you they represent the injured party. The attorney may try to get information from you that you should not share with anyone but your insurer. If you have any doubts about the validity of a caller or an unannounced visitor, call NIA or your insurance broker to confirm the identity of that person before answering questions or providing any written information.

Your insurer may settle claims before a lawsuit is ever filed. Nonprofits Insurance Alliance encourages those who have been injured through the clear liability of one of our nonprofit members to present evidence of damages and a demand for settlement before suing. If the demand is in line with the damages, settlement can often be reached before either side incurs legal costs.

Despite all of our best efforts, lawsuits will inevitably be filed in certain cases. The information in the next chapters explains that process and your role in it.

Chapter 2: Lawsuit basics: When, what, where, and how.

The privilege of filing a civil lawsuit against someone is founded on the principle that citizens have obligations and duties to one another. Failure to fulfill these obligations, or breach of a duty that results in injury or damage to another, gives the injured or damaged person the right to seek recovery.

There are two sides to everything and lawsuits are no exception. The person bringing the lawsuit is called the plaintiff. There can be one or many plaintiffs in any lawsuit, but they all will be listed in the lawsuit.

The person(s) and/or organization(s) being sued are the defendant(s). Besides naming people or organizations, the lawsuit will also name “Doe” or “Roe” defendants. These are people or organizations unknown to the plaintiff when the suit was filed, but who the plaintiff may want to bring into the suit later.

For example, a plaintiff may slip and fall at your fundraiser. The injured person sues your organization and several “Doe’s” or “Roes.” In the course of the lawsuit, it is discovered that the reason the person fell was because Acme Janitorial used the wrong kind of wax on the floor. If there were no “Does,” the plaintiff could not add Acme Janitorial to the list of defendant(s). In legal parlance, the plaintiff(s) and the defendant(s) are the parties to the suit.

When can a lawsuit be filed?

In each state there are various statutes of limitations or time limits in which a lawsuit must be filed for damaged persons to protect their claims and preserve their rights. In cases claiming bodily injury, persons who are injured must have concluded their claim within the statute of limitations date of the incident, or file a lawsuit by the close of court on the statute anniversary of the incident, if they wish to pursue the claim.

Minors (children under the age of 18) enjoy additional protection under the law. Their statutes of limitations do not run until their 18th birthday. Also, persons with mental deficiencies may have no statutes of limitations if they cannot appreciate their duties under such statutes.

What court will be used?

In most states, there are two or three levels of courts where most of the lawsuits will likely be heard. These are Small Claims, Municipal, and Superior Courts (or other names in some states).

Small Claims Court has a jurisdictional limit, usually anywhere from $5,000 to $10,000. Claims for larger amounts cannot be filed in Small Claims. Attorneys are not permitted in Small Claims Court. The parties represent themselves.

Municipal Court has a maximum level of recovery, usually in the range of $26,000. Small auto collisions and small property damage lawsuits are often filed in Municipal Court. Note: Some states do not utilize Municipal Courts. Any suit that is not subject to the Small Claims Court jurisdiction in that state will be filed in Superior Court.

Superior Court is where most of the lawsuits in which nonprofits are likely to be involved in will be filed. There is no limit to the amount of damages that can be awarded in Superior Court.

Federal Court is the most likely place for employment cases* involving allegations of discrimination or harassment. Cases involving out-of-state parties are also candidates for Federal Court.

*In most states, employment cases must first be filed with a state or federal administrative agency before a lawsuit can be filed. NLRB and EEOC are two examples of federal agencies. If you receive such an administrative action, usually called a Charge or a Complaint, you must report it to your insurer and broker just as if it was a full blown lawsuit.

Where will the lawsuit be filed?

The geographical location of the court depends on where the incident or alleged wrongdoing happened, where the plaintiff lives, or where the defendant does business. The lawsuit is usually filed in the county where the event happened, but there are exceptions. If the plaintiff lives in a different 4county, the court may permit the lawsuit to be brought in that county rather than the one where the event occurred. Sometimes the attorney for the plaintiff will file the lawsuit where it is convenient for the law firm. In those cases, the attorney for the defense will ask the court to return the case to the proper county or the correct jurisdiction. This is called “asking for a change of venue.”

How will I know a lawsuit has been filed?

That is a good question. You may have a lawsuit filed against you and/or your organization, but not know about the lawsuit until it has been served. Sometimes lawsuits are filed with the court to preserve the statute of limitations discussed earlier, but not immediately served. Typically, you will not know that a lawsuit has been filed until you are served. You may be served with a lawsuit when a process server shows up on your doorstep or when you receive a large package of unfamiliar documents in the mail.

As a practical matter, it is useless to avoid being served a lawsuit. If you or your organization have been named in a lawsuit, you or your organization will eventually be served. It does nothing but antagonize the parties when people try to avoid service or assume that service has not been completed because they did not touch the papers left on the desk, or because they received the papers via the mail.

Remember that service by mail is recognized by the courts and the clock starts running five days after the date those papers were mailed to you. If they are left on your doorstep and not given to anyone in person, service is probably still valid and the clock has begun ticking.

Chapter 3: Yikes! I’ve been served with a lawsuit!

The first thing to remember when served with a lawsuit is, don’t panic! If you have documented all incidents properly and forwarded this information to your insurance broker, this lawsuit will probably not be a surprise to you or your insurer.

The second thing to remember is that the clock is ticking. What clock? The 20-day or 30-day clock. In most states, the person or organization served has 30 days from the date of service to respond. While it is possible for the defense attorney to request an additional 30 days from the plaintiff attorney, the plaintiff attorney is not obligated to grant it. In most jurisdictions, no extension can be granted without notice to and approval of the court where the suit is filed. In Federal Court, you only have 20 days from the date you were served to respond and extensions are rare.

Because of these very serious time constraints, it is important to take the following steps immediately upon being served with a lawsuit:

- Note the time and date you were served with the lawsuit directly on your copy of the lawsuit.

- Make a copy of all of the papers you have received, keeping one for yourself and sending the original to your insurance broker.

- Call your insurance broker to let them know that lawsuit papers are coming.

Your first inclination may be to talk with people in the office about the lawsuit. Don’t do it. There have been many cases where a disgruntled employee has given information on a lawsuit to the other side, which has proven to be very detrimental. And never, ever call the plaintiff or their attorney.

Mentally prepare yourself to have this lawsuit be a part of your life for a while, but resolve not to let it consume you. Establish a file in a locked cabinet and stay organized and on top of the paper flow that is sure to follow the initial lawsuit. Just as you have relegated this lawsuit to a file in your office, do your best to make it just another of the many projects in your life. It will need attention, for sure, but it should not rule you.

Some folks erroneously think that if the lawsuit is unjustified, it will be easy to get it dismissed early in the process. Consequently, they take the lawsuit process less seriously than they should. In some cases, a “summary judgment” will be granted and the plaintiff will not be entitled under the law to pursue their claim. However, these situations are rare and you should not count on this happening, no matter how ridiculous you believe the case to be.

The courts have demonstrated that they will bend over backwards to give the plaintiff every opportunity to put the case before a jury. Even if your attorney is successful at getting a case dismissed, the plaintiff may appeal the decision, which can easily add two or three years and tens of thousands of dollars to the litigation.

What happens if I don’t “beat the clock”?

It is extremely important to get a copy of the lawsuit to your insurance broker immediately. The plaintiff’s attorney can enter a default judgment against any defendant who is late in filing a response by even a single day! This means that the court records a judgment for the full damages claimed by the plaintiff against you or your organization. The judgment is as final as a verdict after a trial, and it gets recorded even though there has been no trial, no discussion, no showing of fault, no anything. It gets filed just because you didn’t respond in the time required. Period.

There can be relief from a default judgment, but the longer it is in place before anyone challenges it, the harder and more expensive it is to get the default judgment set aside. A motion to set aside the default must usually be made within six months after the notice of default was filed. These motions are granted for a very few acceptable reasons, such as a mistake, inadvertence, or excusable neglect. Failing to take prompt action on the lawsuit ,or ignorance of the lawsuit process, usually will not qualify as acceptable reasons. After a short period, a default can be set aside only if fraud is involved.

A default can be entered only after proof of service is filed with the court and the minimum time to respond has elapsed. This means that if you get a notice of a default, the lawsuit was served at some time to someone presumed to represent you or your organization. Just because the papers did not make it to the executive director or other person in charge, does not mean the lawsuit was not served and is not valid.

Every organization should designate one person to accept service of lawsuits. Instruct employees, volunteers, directors and officers not to accept service, but to refer service to the appropriate person. The process server who comes to deliver the lawsuit should be told where they can find that person. Remember, it never improves the situation to evade service of a lawsuit. It is best to establish a protocol so these important papers are delivered to the right person immediately.

The bad news for you is that your insurer may claim that a default judgment voids the policy because they did not have a chance to investigate and defend the lawsuit. Remember, insurance policies typically require the insured to notify the insurer immediately whenever a claim is made or a lawsuit received.

Failing to make proper and prompt notice to your insurer can void the contract and deprive you of insurance coverage.

What if the media calls?

If your nonprofit organization is named in a lawsuit, even one that is unjustified, it has the potential to damage your reputation in the community. Adequate preparation is essential for an effective response to the media during a crisis. The following guidelines will enable you to turn a potentially risky activity into an opportunity for your organization:

- Designate a media spokesperson and at least one back-up. These individuals should be trained in advance of a crisis about what is and is not appropriate information to release to the media.

- Make sure that everyone knows the identity of the designated spokespersons(s). Non-authorized persons, including staff, volunteers and board members, should not talk to the media.

- Do not admit wrongdoing. Keep in mind that anything anyone in a position of authority says to the media can be used against the organization in any litigation that results. As tempting as it might be to admit liability to “get it off your chest,” you can be sure that this admission will greatly diminish your attorney’s ability to defend you in a lawsuit.

- Remember that “no comment” says a lot. “No comment” fills pages in the minds and imaginations of readers and viewers. What is the organization trying to hide? Isn’t there anything it can say about this dreadful event? Count on the fact that a skillful reporter will find someone to comment about the incident—including your organization’s handling of the crisis. Remember to think carefully about what you do say and what you don’t say.

- Stay calm and “on message.” The key is focusing on the message you want to deliver. Advance preparation is necessary.

- Deliver a positive, truthful message about your organization. While it is important not to evade a reporter’s questions altogether, always begin your response with a positive message about your organization, which incorporates your commitment to safety. For example, “The mission of the Youth Activities Center is to promote safe recreational activities for disadvantaged children in this community. Our commitment to safety is reflected in our safety training programs for athletes, rigorous screening and training program for volunteer coaches, and the provision of appropriate safety gear for all participants.”

- Do not improvise your answers. If you do not know the information asked by the reporter, admit that fact and if appropriate, pledge to find out as soon as practical. Establish a time and place to provide information updates.

- Show concern and compassion. Compassion for victims and those who are disadvantaged by circumstance, physical disability or economic status is at the heart of the work of many community-based nonprofits. The public expects a nonprofit spokesperson to demonstrate compassion. Never dismiss an incident where victims are involved as inconsequential.

Which insurer will handle the lawsuit?

You have been served with a lawsuit. You’ve identified and recorded the date you were served and sent the papers along to your insurance broker. Now what? Your insurance broker will forward it to the appropriate insurers, depending on the type of claim and whether the lawsuit qualifies for defense by an insurer.

For example, if you’re served a lawsuit regarding an auto collision, your insurance broker will send it to your auto insurance company. If the incident is a slip and fall at your facility, your insurance broker will send it to whatever company provides your general liability policy.

If there is a question of whether an insurance policy will defend the lawsuit, your broker will send that lawsuit to any insurer that might have an obligation to defend or indemnify you or your organization for the claims in the suit.

If your insurer determines that the policy does not cover that lawsuit, your insurer must tell you that in writing and explain exactly why the policy does not apply. When an insurer has an obligation to defend the lawsuit, the insurer will send you a letter telling you what lawyer the insurer has hired to represent you and/or your organization. Sometimes, your insurer may send you a letter that says that it agrees to defend you, but only under certain conditions. That is called a “reservation of rights” letter.

What is a reservation of rights letter?

A reservation of rights letter explains that, because some causes of action in the lawsuit are not covered by the policy, the insurer will defend without becoming obligated to pay damages awarded as a result of acts not covered by the policy. It is important to remember that the reservation of rights letter does not mean an insurance company is not going to defend the organization. It means that the insurance company will defend the organization, but the company is making sure you understand that some of the allegations in the suit may not be covered.

These letters are often long and difficult to read. This is because the insurer must spell out exactly why it is reserving its rights. It may be that both negligent and intentional acts are alleged in the suit. There may be questions as to whether the employee or volunteer was acting in the course and scope of their relationship with the organization. Insurance typically does not cover damages awarded as a result of certain intentional acts, such as fraud, assault, intentional infliction of emotional distress, punitive damages and others. If it did, there would be no incentive for anyone to behave reasonably and responsibly. Without a reservation of rights letter, an insurance company might find itself in the position of providing coverage for an uninsurable act.

If you feel that a reservation of rights letter was sent incorrectly, or you have additional information that may have bearing on the case, you should write to the insurer or have your broker write to the insurer and ask for another review of the coverage question.

In most cases that we have seen, the case will be defended, settled if appropriate and concluded without any further reference to the reservation of rights. Nevertheless, if you are uncertain you may also wish to have your corporate attorney review the language and discuss it with you.

In some rare instances, there could be a conflict of interest between you and the insurer, or it could become clear that the majority of damages claimed result from uncovered acts that happened but are not insured under the policy or cannot be insured as a matter of public policy. In those instances, the insurer must tell you its coverage position and may be required to offer you the option of a separate attorney at the insurer’s expense.

What are all of these papers?

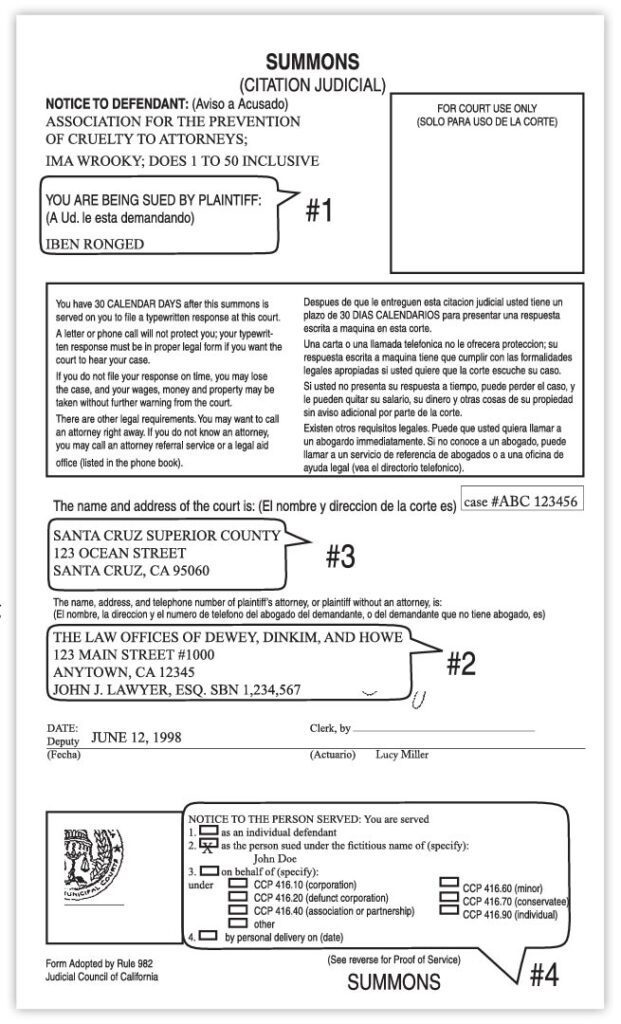

When a lawsuit is served, there are two parts: a summons and a complaint. The summons is a notice to you and/or your organization that you have been sued. The complaint tells you what the suit is about and what the person suing wants. On the following four pages, we will review these two parts.

The summons:

The top paper is the summons. The summons is a very important piece of paper. The sample summons below shows:

- who has filed the lawsuit,

- what attorney represents that person, and

- what court the suit will be heard in

The summons will also tell you exactly who is being served. On the bottom third of the sample summons it lists who or what is being served with this lawsuit.

- If you are being served as an individual, it will say so. If you are being served on behalf of your organization, it will say so. If you are being served as a previously unnamed defendant, you will see language referring to “Doe” defendant, just as in John Doe.

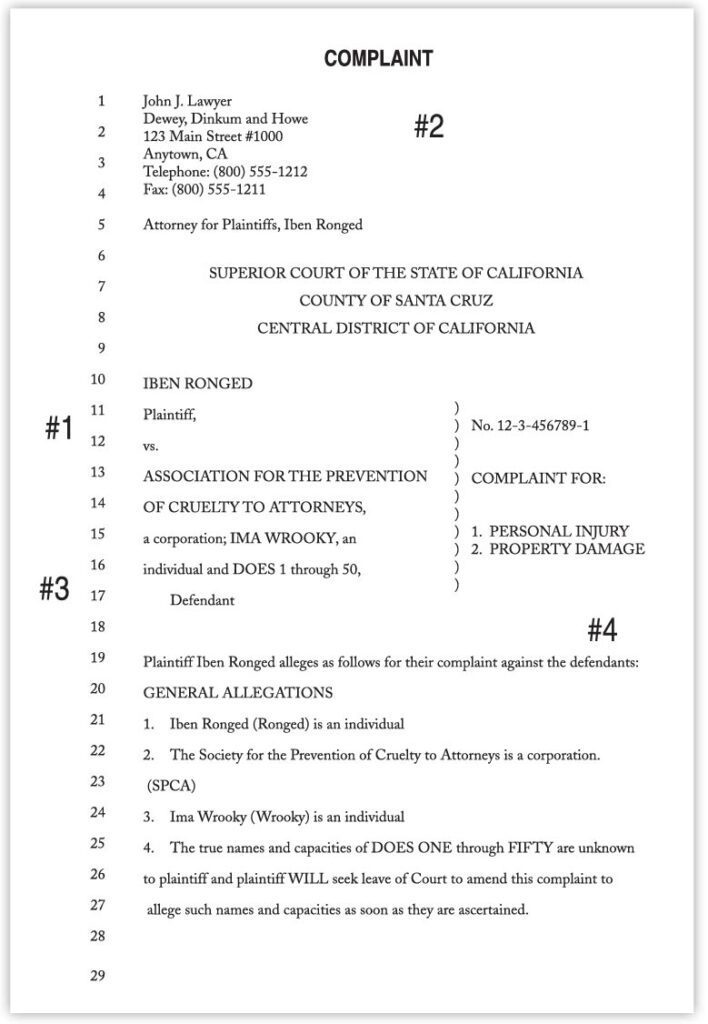

The complaint:

The complaint is the rest of the papers you receive except for the top page (the summons). In some cases, other documents are included with the complaint. A statement of damages (usually a huge number, unrelated to the merits of the case) and a notice from the court extolling the virtues of arbitration or mediation are the most common attachments. The complaint is a description of all the ‘bad’ things you are supposed to have done to the plaintiff and what the plaintiff has suffered as a result of your actions.

A sample complaint follows with the following information highlighted: The first page of the complaint, the title page, will show

- the name of the person or persons who are suing you,

- the name of the attorney representing the plaintiff,

- all of the people or entities who are being sued, and

- what the suit is about.

Generally speaking, it is not a good idea to read the complaint right away. Most people get very upset at what the lawsuit claims to have happened. Remember, lawsuits are all written in the same manner and use the same type of language. This language has developed over the years and is consistent from lawsuit to lawsuit.

Many counties have adopted a “fill in the blank” form complaint where boxes are checked and a few paragraphs describing the particular event leading to the lawsuit are inserted in the appropriate places.

Remember that most of the language used is standardized from complaint to complaint. While this one may rant and rave about you or your organization, you will be comforted to know that all complaints rant and rave in the same fashion.

Remember that Nonprofits Insurance Alliance sees many lawsuits lodged against a wide variety of nonprofits. We are familiar with the language used in lawsuits. We understand that the claims are most likely exaggerated and do not represent your side of the story.

Yes, we know that you may, in spite of the preceding warning, decide to read the complaint.

On the second or third page, after a lot of description about what kind of an organization the plaintiff believes yours to be, a paragraph will begin with “on or about” or words to that effect, and will be followed by a date. That is the date on which the subject of the lawsuit is alleged to have occurred.

If, for example, the lawsuit is because someone ran a stop sign on January 2nd, then the complaint would refer to “on or about January 2nd.”

There is usually no cause for either alarm or rejoicing if the date cited in the lawsuit is not exactly the same date that you remember the incident happening. However, be sure to advise the attorney assigned to represent you of any discrepancies.

Chapter 4: What are the steps in the lawsuit process?

All lawsuits begin with the process of gathering information. Once sufficient information is gathered, the parties will determine whether to try to settle the lawsuit out of court or to take it to trial. The information gathering process in litigation is called discovery.

What is discovery?

Discovery is the process during which both sides find out what the other side knows. There are several standard and common discovery procedures which occur during the course of a lawsuit.

Initially, your attorney may wish to meet with you or the relevant staff people and get a feel for your version of what happened. If the incident that is the basis of the lawsuit was already investigated by a representative of your insurer, the attorney assigned to the case may not need to meet with you right away. Do not, under any circumstances, speak with or give information to the plaintiff or their attorney.

Interrogatories:

The first item of discovery is a series of formal questions called interrogatories. There are two types of interrogatories: form and special. Form interrogatories are just what the name implies— standardized questions on a preprinted form. The person sending form interrogatories simply checks the boxes for the questions they want answered and sends the form to the attorney representing that party. In most cases, attorneys can answer form interrogatories with a little help from you. Typical interrogatories will also ask you for any documents you have related to the case or the incident (photographs, statements, insurance policies, repair invoices, video tapes, personnel records, etc).

Your attorney will send form interrogatories to the plaintiff(s) that ask the injured party for the names and addresses of all treating physicians, documentation of any lost earnings claimed, and so on.

Special interrogatories are questions that address more specific issues concerning the lawsuit. Your attorney will probably need your help in preparing answers to special interrogatories.

Special interrogatories may not be sent by all parties to all parties. They may be sent later in the lawsuit and more than once. Again, it is very important to give prompt and full attention to these questions so that your attorney can do the best possible job of representing you and your organization.

When you receive the interrogatories, either form or special, you must answer them to the best of your ability. These answers are under the penalty of perjury. This means that lying or omitting information may be grounds for criminal action.

Once interrogatories have been received, you and your attorney have 30 days to prepare the answers, put them in the proper format, and return them to the party who asked the questions. If you have any difficulty in answering any of the questions or locating any requested documents, you should contact the attorney assigned to you right away so that they can be of assistance.

There will be occasions where obtaining or finding old records will be very difficult, time consuming, and a real pain in the neck. Unfortunately, the courts do not recognize any of these as legitimate reasons for not providing all of the documents or information requested. We have found that the sooner you attack this project, the easier it is to complete. Again, if you are having a problem complying with the request for documents, contact your attorney sooner, rather than later.

Depositions:

The next most common procedure in the discovery process is depositions. A deposition (often abbreviated as depo) is delivering testimony under oath. This occurs outside of court and before trial. A deposition notice or subpoena is sent to the party whose testimony is sought. The subpoena or notice tells that person of the time and place of the deposition.

In most lawsuits, depositions are scheduled informally and without subpoenas. The plaintiff’s deposition is usually conducted at the plaintiff’s attorney’s office and the defendant’s deposition at the defense attorney’s office. Meeting rooms at airports and hotels, and offices of the court reporter are also commonly used for depositions. While your attorney will make every effort to accommodate your schedule, in cases with many parties, that may not be possible. Nevertheless, you must attend a deposition for which you have been scheduled, no matter how inconvenient. Depositions may last anywhere from less than an hour to several days. Most are completed in half a day. You should remain flexible and not schedule other appointments for the same day as your deposition. Frequently, depositions need to be rescheduled because of attorneys’ scheduling conflicts with other cases. There is little you can do in those cases other than work with your attorney to reschedule the deposition.

Your attorney will meet with you before your deposition to go over the process and to review what questions are most likely to be asked. This is also a time to ask any questions you have concerning the case.

At the start of the deposition, you will be sworn in as a witness and a court reporter will be present to take down all the questions and answers. After the deposition is complete, it will be transcribed into a booklet that you will have the opportunity to review and correct.

Minor changes are usually not commented on by the plaintiff’s attorney, but you can be sure that any major changes, such as a “yes” answer that is changed to a “no” will draw serious scrutiny from the plaintiff’s attorney.

As always, honesty is the best policy. The important thing to remember is that all of the testimony given in a deposition is under oath and is admissible in court should the matter go to trial.

Therefore, your answers must be accurate, truthful, and complete to the best of your ability and recollection. If you don’t remember something or don’t know the answer to a question, say so. That is an acceptable answer. Always follow all special instructions given by your attorney.

Depending on the case, there may be depositions of people on your staff or from your organization. Your attorney must have the cooperation of your organization and your staff, whom you should make available when necessary.

While the interrogatories will be fairly early in the lawsuit, depositions may not take place until much later. Cases often take between one and two years after the lawsuit is served to get a trial date.

Consequently, your deposition testimony may not occur for several months after the lawsuit is served.

Will the case go to trial?

Probably not. The good news is that about 97% of all lawsuits are settled or resolved in some fashion before going to trial. The remaining 3% are tried to verdict. There are several processes by which resolution, short of trial to verdict, can occur. More and more jurisdictions are requiring cases either to go to non-binding arbitration or to mediation before getting a date for trial. Other cases are resolved late in the litigation process at a court-required settlement conference or even on the courthouse steps the morning of trial.

Mediation:

One of the most common ways to settle a lawsuit before trial is mediation. Mediation is most productive when the parties to the lawsuit agree that the plaintiff is entitled to recover something, but disagree as to how much. The parties will then agree to have a neutral third party manage discussions leading to an agreement to settle. Mediators do not decide cases. The parties reach agreement with the help of the mediator. If an agreement occurs, settlement monies will be paid in exchange for a release of all claims from the plaintiff and a dismissal of the lawsuit which ends the case.

Arbitration:

Other cases are resolved by arbitration, either binding or nonbinding. Arbitration is the private, judicial determination of a dispute by an independent third party. Both parties agree to submit their case to an arbitrator, who will make decisions regarding liability, damages, or any other issues submitted. In the case of binding arbitration, the parties have agreed that whatever finding the arbitrator makes is permanent and agree to abide by those decisions. In non-binding arbitration, the decision of the arbitrator is advisory only. Either side can reject the findings of the arbitrator in a non-binding arbitration and continue with the normal process of litigation.

Trial:

Most cases that go to trial go for one of two reasons. One reason is that the plaintiff wants far too much money for the nature of the injury and no agreement can be reached between the parties. The other common reason cases go to trial is when the defendant is convinced that either the obligation owed to the plaintiff was met, or that no duty to the plaintiff ever existed and the plaintiff has no right to recover anything from the defendant.

If you or your organization goes to trial, it is very important that you or an appropriate member of your organization be present in the courtroom during the trial. Your attorney and your organization must agree on who should be present and during what time frame.

We understand that the entire lawsuit process, up to and including a trial, is a major inconvenience. However, it is very important to the success of your lawsuit that each step of the process is taken seriously, including attending the trial, if necessary. Your attorney will strive to accommodate your schedule, but often there is little that can be done to change the court’s schedule.

They never should have settled that case!

Many nonprofit staff and board members are offended by the idea of settling a lawsuit. “Your insurer paid money to that flake? They paid how much? The person wasn’t really hurt at all!” Sound familiar?

If your insurer settles a case that you believe ought to have been defended through trial, keep in mind that juries and their verdicts are unpredictable. Insurers must evaluate the potential for an adverse verdict on the basis of their experience dealing with similar cases.

On the other hand, NIA sometimes finds it necessary to try cases that could be settled for a nominal sum to protect the ability of our members to continue their programs and to make “good law” to protect the entire nonprofit sector. We do not make this type of decision lightly, but we take our obligations to our members seriously. You may be surprised to know that the average daily cost to try a case is $3,000. Even the simplest of cases take three to five days to complete. Experts cost hundreds of dollars an hour for their investigation and opinions and thousands of dollars at trial. Jury and court reporter fees must also be paid. Cases with multiple parties or complex issues of liability or damages can easily take three to four weeks to try and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. All of these factors need to be considered before the decision is made to go to trial.

If you are concerned about how the case is progressing, contact your attorney and ask. You may also contact your insurance broker. If you are insured by Nonprofits Insurance Alliance, you may also contact our Claims Department at 800-359-6422.

Chapter 5: Conclusion.

Foremost, when an incident happens, make sure that the injured party receives immediate, appropriate care. After the injured party is cared for, document the incident and report it to your insurance broker, whether you think there will be a claim or not.

Insurers cannot investigate an incident they do not know about. And, it is often very difficult to get the facts from witnesses who were there when a year or more has passed between the incident and the time the lawsuit is served.

Nonprofits Insurance Alliance often chooses to investigate incidents even if they have not yet become claims, if we think our early research will be helpful in the future handling of the claim.

At the time of an incident, many people will say, “I’m okay,” “That’s all right,” or “I’m not hurt,” and when they make those statements, they probably believe them. We have found that many of these claims turn into lawsuits and there is no one to talk to or witnesses to interview and no scene to investigate because it was never reported to us, the insurer. Your organization will be much better off if you have given notice of an incident.

Lawsuits are traumatic, time-consuming, expensive, difficult, and a fact of life. You can strengthen your position in a lawsuit by carefully documenting the situation, forwarding the lawsuit promptly to your insurance broker, and cooperating with the claims investigator and attorney by providing honest answers and prompt information. This will make those cases that turn into lawsuits much easier to defend and allow them to be managed much more successfully.

In summary, we offer a few tips:

- Make a note of how and when you were served with a summons and/or a complaint. A summons must be answered in 30 days or less depending on where it is received and by whom. Don’t dodge service. It accomplishes nothing and can create difficulties for your attorney.

- Don’t alter your records. You will want to look at your incident report to see what happened, but make no changes, additions, or deletions to any documents. Most importantly, do not dispose of any documents you think may be harmful. Someone probably knows that piece of paper exists and has a copy. You will only look foolish to the other side and dishonest to the court.

- Notify your insurance broker immediately. Make a complete copy of the lawsuit and send the original to your insurance broker and call to let them know it is in the mail. No matter how upset you are that a lawsuit was filed, ignoring it will not make it go away. Ignoring it can jeopardize your insurance coverage and even make you lose the case by default. It is absolutely critical that the response be handled correctly.

- Don’t talk about the case except with the insurer representative or the defense attorney hired to represent you and/or your organization. Never, ever call the plaintiff. Whatever caused the lawsuit has not been resolved and you will not be able to do anything about it at this point. It is extremely important not to discuss the case with others, and particularly not with the plaintiff or their attorney. Beware of discussing the lawsuit with co-workers. “Walls have ears” and you never know who is listening. There have been many cases where a disgruntled employee has given information on a lawsuit to the other side which has proven to be very detrimental.

- Do cooperate in obtaining all of the documents, records, or other information when requested by your lawyer. Speedy cooperation is essential. Be sure the originals are in a safe place and send the records exactly as they have been maintained.

- Don’t overstate or understate the facts as you see them when you talk to your insurer or your defense attorney. It is likely that your insurer and the defense attorney assigned to represent you and/or your organization will require an in-depth discussion concerning the circumstances or facts of the incident. Be sure you disclose all facts, not adding anything or leaving anything out. There is no advantage to withholding or ‘modifying’ information. In the end, the truth will come out. The one thing all defense attorneys hate is a surprise. If there is something that you know about an incident that is relevant to that incident, or even if you think it isn’t important, you must come clean and tell your attorney EVERYTHING. The worst possible case is for an attorney to be surprised on the eve of trial with a fact that changes the entire complexion of the lawsuit.

- Don’t let politics or emotions prevail over good sense. We know a lawsuit can be a blow to your organization’s ego and can jeopardize your good reputation. Your first reaction may be to want to disclose the “real facts” to the public to absolve your agency of wrongdoing. Don’t do it! When an organization does this, it can be very damaging and make it harder for your attorney to help you and to properly handle the claim. Designate one person as the spokesperson for the organization and make sure that person has been trained to work with the press.

- Resolve to do this right. This lawsuit will likely be a part of your life for a while. Resolve to take it seriously, but don’t let it consume your life. Sometimes the steps in the lawsuit process will seem cumbersome, repetitive and unnecessary. Despite the hassle, provide accurate, thorough information.

Appendix A: Glossary.

The following is a general list of terms for your reference. Note that not all terms have been used in this e-book.

action – a lawsuit

actual damages – real damages awarded for the actual and real loss or injury; synonymous with consequential damages

addamnum – the damage; the portion of the plaintiff’s complaint which contains the statement of his or her monetary loss or the damages he or she claims

adnausea – to the point of nausea (a Latin phrase far more often applicable in the course of litigation than it is actually used)

agent – one who acts for or in place of another by authority from them

agent for service of process – the company or individual the organization designates to accept service of summons and complaints

allegation – the statement in a pleading of that which the party intends to prove

answer – the reply filed by the defendant’s attorney to the complaint

arbitration – the process by which a neutral third party makes a decision about the lawsuit

attorney-client privilege – a legal exemption from disclosure of communications between attorney and client

binding arbitration – the decision of the arbitrator is final burden of proof – the duty of a party to establish a claim or defense; the “weight” of the burden depends on the nature of the claim or defense (see “preponderance of evidence,” “clear and convincing”)

cause of action – in pleading, distinct allegations of fact by the plaintiff which purport to support a legal right of recovery, remedy or relief

charge – another name for a complaint, usually found in employment cases before administrative agencies

civil law – that body of law dealing with the enforcement of civil rights as distinguished from criminal law

clear and convincing – the weight by which the burden of proof must be established in certain circumstances: it is evidence of such convincing force that it demonstrates, in contrast to the opposing evidence, a high probability of the truth of the fact(s) for which it is offered—this is a higher standard than preponderance of evidence

compensatory damages – damages such as will fully compensate the injured party for his or her loss

complaint – document filed with the court that contains all the accusations against the defendant; the actual lawsuit

court ordered arbitration – a formal arbitration proceeding scheduled through the court. If either side doesn’t like the arbitrator’s award, they may request a trial de novo within 30 days.

cross-complaint – a lawsuit by a defendant against another defendant or the plaintiff that has the same case number as the original complaint

default judgment – a judgment against any defendant who does not respond to the lawsuit in time can be recorded by the plaintiff and has the same effect as a verdict if it is left to mature

defendant – the person or organization being sued

demurrer – a pleading by the defendant which is often used to assert that plaintiff is not entitled to relief even if all of the material facts pleaded are assumed to be true

de minimis – trifling, from the Latin phrase “de minimis non curat lex”; the law does not take notice of or concern itself with trifling matters

de novo – anew; a second time; often used to denote the circumstance in which a matter, previously adjudicated, is determined again with no regard to or influence from the prior adjudication (“trial de novo”)

deposition – testimony taken under oath before the trial discovery – the process of formal investigation by both parties, the means by which each side finds out what the other side knows

doe defendant – a defendant sued by the fictitious name “Doe” because the party is unaware of the “Doe’s” true name or capacity; the reason for use of the “Doe defendants” is to avoid the bar of the statute of limitations with regard to subsequently discovered responsible parties

duty – that obligation to act or refrain from acting on which one legally owes to another

exclusive remedy – doctrine created by statute whereby certain claims give rise to a specific remedy to the exclusion of any other

exemplary damages – see “punitive damages”

fictitious defendant – see “doe defendant”

evidence – any means by which a matter of fact is submitted for establishment or disproof

filing – the act of giving a complaint to the court in which the complaint is date-stamped and given a case number and a summons is issued

in limine – at the very beginning; usually used to describe motions made immediately before and preliminary to trial

impeach – to challenge the veracity of the witness by offering evidence which contradicts the witness or otherwise indicates he is unworthy of belief

independent contractor – one who contracts to do a piece of work by their own methods and judgment and without the control of their employer, except as to the results

injunction – a remedy in equity whereby the defendant is forbidden to do some act or restrained from continuing an act or course of conduct; under certain circumstances, the defendant may be commanded to take particular action

in personam – with regard to a person; an action or proceeding “in personam” is one directed against a person, and “in personam” jurisdiction is jurisdiction over the person

inter alia – among other things

interrogatories – written questions asked by one party to another

intervention – a procedure by which a person, not a party to an action, becomes a party

judgment – the official decision setting forth the rights and obligations of the parties to an action who have litigated and submitted their dispute for determination; following a jury trial, it is the official memorialization of the jury’s verdict

jurisdiction – the authority by which the courts and judicial officers act that includes the authority to take cognizance of and decide cases; involve parties; enforce sentence, judgment, or decree, to do justice

jury – in civil litigation, a prescribed number of individuals selected according to the law, and sworn to determine the truth of matters of fact presented by the evidence

jury instructions – statements of law provided to a jury then charged with determining the truth of the matters of fact and rendering a verdict under the law presented in the jury instructions

lawsuit – an action or proceeding under civil law liability – legal responsibility or obligation

limitation – a statutorily set time period during which an action must be brought and at the end of which such action may not be initiated; established statutorily, hence the term “statute of limitations”

litigation – a judicial contest or controversy; the process of prosecuting a lawsuit

mediation – a process by which a neutral third party attempts to get opposing sides to agree

motion to compel – a request that court orders someone to do something, usually to appear for a deposition or to answer a particular interrogatory

motions – formal requests to the court to either take an action or make a decision about some aspect of the lawsuit

non-binding arbitration – the decision of the arbitrator is not final

non sequitur – it does not follow; used often as a noun to describe something that does not relate to or follow from something else, often that which precedes

non-suit – a type of judgment rendered by the court against the plaintiff because the plaintiff has failed to introduce evidence sufficient to prove a case for discovery or remedy

order – any direction of a court or judge, normally entered in writing party – a person taking part in a lawsuit

personal service – a process server hand delivers the summons and complaint to the individual defendant or the representative of the organization

plaintiff – the person or organization bringing the lawsuit

pleading – the process by which the parties to a lawsuit present written statements of their contentions

prayer – relief and/or damages sought as set forth in a pleading

preponderance of evidence – the greater weight of evidence; that evidence that has more convincing force than that opposed to it

proximate cause – a cause which, in natural and continuous sequence, produces damage, injury, loss or harm and without which such damage, injury, loss or harm would not have occurred

proof of service – a document filed with the court under penalty of perjury that the summons with the complaint was served (given to) the defendant named on the proof of service

punitive damages – damages awarded to a plaintiff over and above what will compensate him for his injury and for the purpose of punishing the defendant, making an example of him or her, and/or deterring future conduct of the nature supporting award

requests for admissions – force the responding party to admit or deny the truth of a fact or the genuineness of a document; failure to answer a request for admissions timely eliminates the right to object to the requests—if you don’t respond, the asking party can request the court to order the requests “deemed admitted,” meaning that you can’t later deny them

service – delivery of the summons with a copy of the complaint to the defendant(s)

service by mail – sending the summons and complaint to the address of the defendant

service of process – the formal name for delivering the summons and complaint to defendant(s)

settlement conference – a court-ordered session a few days before trial, in which the parties try to resolve the case before trial

statement of damages – a document filed with the court stating how much the plaintiff wants for their case

statute of limitations – the time in which a lawsuit must be filed to be valid

subpoena – an order from the court to appear somewhere, usually at a deposition or at trial

subpoena duces tecum – to bring all records, bills, or other documents requested with you to your deposition

summons – notice to the defendant(s) that a suit against them is on record at the court

trial – a formal examination of evidence before a judge, and typically before a jury, in order to decide guilt in a case of criminal or civil proceedings

trial de novo – a formal rejection of the arbitration decisions; a request for a “new trial”

venue – the location where the lawsuit is to be filed

Appendix: Member resources.

See all free and discounted risk management services available to nonprofits insured by NIA.