This report is one of a series of Occasional Papers that both the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and California Community Foundation periodically issue to inform interested parties about selected current topics. Both foundations provided funding to develop and distribute this paper. The California Association of Nonprofits facilitated the research and writing of this particular report. We also wish to acknowledge the contributions of the late Terry McAdam to this publication.

February 1987

2022 Edition (35th Anniversary) Notes

- The original version of this thesis (PDF) was printed on an early laser printer and included some photocopied materials in the appendixes. At some point afterward, the original digital file was lost, the printed copy was scanned as a PDF, and the legibility of the document began to suffer.

- In 2022, an updated version of this thesis (PDF) was created to correct these issues.

- The page you are currently viewing is the accessible, HTML version of the updated thesis.

- As something of an epilogue, Pamela Davis reflects on her thesis 35 years later, as well as the implications it has for the current insurance crisis.

Notable changes from the original 1987 thesis and this HTML version:

- Chart 1. Insurance industry cycles has been given an updated design (with the same information).

- A sentence explaining how to get copies of this thesis from the California Community Foundation has been removed from the intro paragraph under the thesis title.

- APPENDIX B has been replaced with links to the Liability Risk Retention Act of 1986.

- Table 2. Primary differences: Captive, risk retention group, and California risk pool has been updated to include corrected data.

- A few small typos have been corrected.

- Minor styling changes (underlines, ALL CAPS, bold) have been made to better satisfy online etiquette.

Preface

It doesn’t seem possible to imagine anyone connected with the nonprofit sector who has not recently heard about some organization and its insurance tribulations. Anecdotes abound and, as this document will attest, nonprofits are confronting serious issues about how to manage their insurance needs. Many organizations are faced with extraordinarily high insurance costs for which they made no plans. Other organizations have actually had their policies canceled. Small wonder, then, that this Occasional Paper makes reference to the insurance crisis.

The staff at the California Community Foundation has become aware of one important aspect of the current situation through its own research and work with others concerned as well. For all of the attention being given to insurance problems affecting nonprofit organizations, there is little information available that clearly describes how and why such problems arose, and what can be done to solve them. It is in the spirit of rectifying the lack of data and options for change that this Occasional Paper has been produced.

With greater awareness of the nature of the present dilemma and, most importantly, with increased options to improve what the nonprofit community can do to help itself, perhaps the day will come when what is now seen as a crisis will be referred to as an opportunity realized.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Some Basics

- The Scope of the Problem

- Causes of the “Crisis”: What Happened?

- Private Nonprofits: Why Are They Vulnerable? What Can They Do?

- Risk Sharing: The Most Powerful Tool Available To Nonprofits

- Existing Nonprofit Risk Sharing Mechanism

- Difference Between Illinois Pools and Available Alternatives

- Potential Benefits of Risk Sharing

- Limitations of Risk Sharing Mechanisms

- Potential Implementation Barriers

- Prospects for Success

- Current Efforts to a Initiate Risk Pool for Nonprofits in California

- Conclusions: Ideas for Action

- What might an individual organization do?

- What should nonprofits ask of legislators?

- Will tort reform eliminate future crises?

- Is group purchasing a solution for your organization?

- How can nonprofits help to establish risk sharing mechanisms?

- What criteria should an organization consider before joining a risk sharing mechanism?

CHARTS AND TABLES

I. Background

Insurance as we now know it began in London, England in the seventeenth century. Merchants and shipowners gathered in coffeehouses to write policies for voyages, each sharing a part of the risk of many different voyages. When there was a shipwreck the losses were shared among many individuals. Many people would each lose a small amount, but no one merchant or shipowner would bear the total loss and be financially devastated. The most successful and largest of these coffeehouses belonged to Edward Lloyd. His coffeehouse became Lloyd’s of London, now one of the most powerful and important insurance groups in the world. [1]

Today, the insurance industry in the United States is a $310 million business which employs nearly 2 million Americans—which is nearly two out of every one hundred Americans in the workforce. Insurance premiums represent approximately 12 percent of the disposable income in this country. Insurance is the fourth largest purchase Americans make (behind food, housing, and federal income taxes.) [2]

The insurance industry is divided into two subgroups of insurers: life/health and property/casualty. The crisis discussed herein is lodged within the property/casualty sector, and is focused in the commercial casualty or “liability” portion of the property/casualty insurance industry. Liability insurance policies are purchased to protect individuals and organizations from losses incurred through accidents which result from their own negligence. For example, if a child is injured at a day care center and it can be demonstrated that the child was injured because the playground equipment was unsafe, the day care center’s liability insurance would pay the medical costs and also legal and settlement costs if the parents of the child sue.

Historically, the property/casualty industry has demonstrated a cyclical pattern of profitability. Unlike most other industries, the property/casualty insurance industry is flexible with respect to capacity. When times are good, insurance companies can increase their capacity, take varied and greater risks, and generally lower their premium rates in order to achieve a greater market share. This results in a change from favorable premium profit margins to unfavorable margins, resulting in profit and loss cycles. [3]

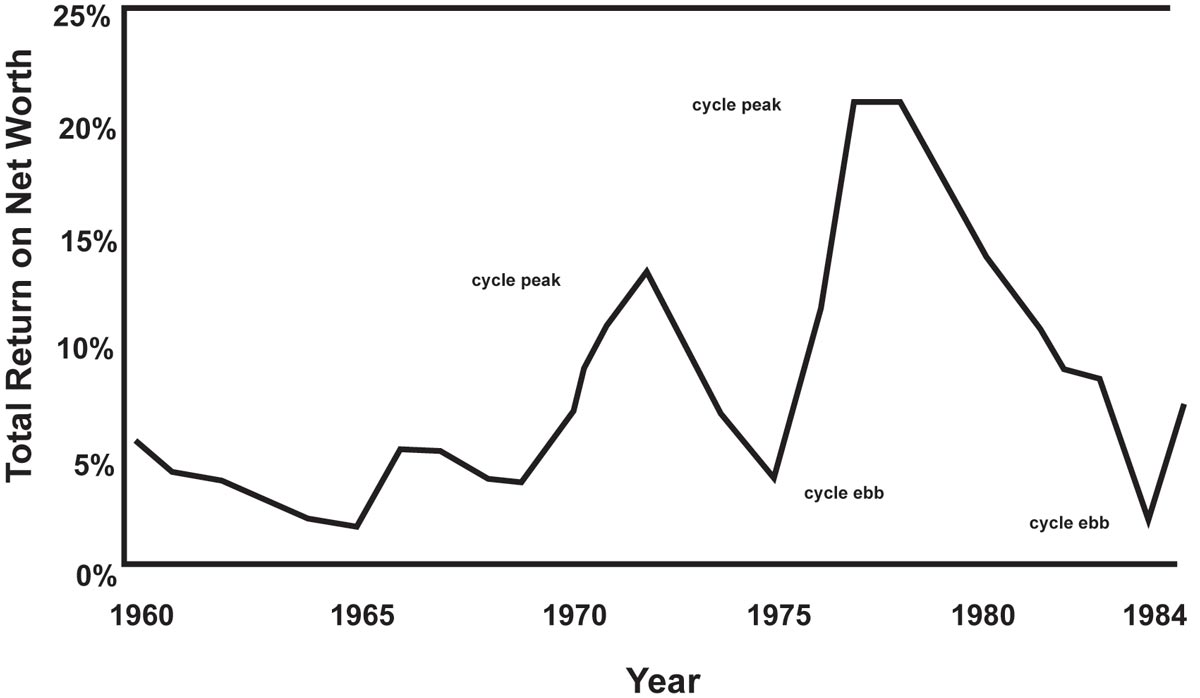

During the last decade the property/casualty insurance industry has experienced particularly dramatic swings of profitability, showing low return to net worth at cycle ebbs in 1975 and 1984 and high return (i.e. high profitability) at cycle peaks in 1972 and 1977-78. Chart 1 illustrates these cycles.

CHART 1. Trends in insurance industry profitability [4]

During the years of high profitability, return on net worth ranged from 14 to 21 percent. During the years of low profitability in 1975 and 1984, return on net worth was below 5 percent. Insurers responded to the lower level of profitability during the recent cycle ebb in 1984, in much the same way as they responded to the 1975 ebb. They dramatically increased premium prices—as much as 1000 percent in some cases—and dropped or refused to renew those policies which they believed were least profitable. In 1987, for-profit and not-for-profit organizations are continuing to experience the effects of these premium increases and diminished coverages.

The focus of this paper is on the impact of the recent insurance crisis on private nonprofit organizations. [5] Nonprofit managers have been bombarded with facts and figures, many of them conflicting, from all sides of the crisis. In response to this confusion, this paper originally was conceived as a working paper designed to outline many potential options for nonprofits to increase the availability and affordability of liability insurance. The realities of the liability insurance marketplace and the ineffectiveness of many of the proposed solutions have significantly narrowed the scope of ideas for action.

In the process of researching this paper it was discovered that there is little that individual nonprofit organizations can do to moderate the impacts of insurance industry cycles. The best solution for dealing with the crisis are those which involve the collective efforts of many nonprofit organizations, and it is those types of solutions towards which much of this paper is devoted. Risk sharing is given special emphasis because of its relatively strong potential for providing both short-term and long-term assistance to the nonprofit sector, and because of recent legislation enabling nonprofit organizations to create risk sharing mechanisms.

II. Some Basics

This section contains three parts intended to promote better understanding of some insurance terminology in general, and liability insurance, in particular. These three parts are: (1) general definition of potentially unfamiliar insurance terminology; (2) descriptions of the various types of liability insurance commonly used by nonprofit organizations; and (3) discussion of important provisions which are part of many liability insurance policies.

A. General Definitions

Captive Insurance Company: A captive insurance company is solely owned by the organizations or individuals it insures. The owner of the captive contribute capital and pay premiums to the captive, and in general, the premiums are used to cover the administrative expenses of the captive and to play claims.

Claims-made Policy: A claims-made insurance policy states that the occurrence and the claim of injury or loss must be reported to the insurance carrier within the effective dates of the policy. For example: A person slips and falls on an organization’s premises in November of 1986, but the incident is not reported to the insurance company until July of 1987. If the claims-made insurance policy began in January 1986 and expired in December 1986, that accident would not be covered under that policy.

Earned Premium: That amount of the annual premium which is proportional to the time passed during the premium year. For example, of an annual premium of $1,000 which is paid to an insurance company, roughly $500 will be considered earned premium when six months of the policy period has passed.

Group Insurance: A group insurance plan is a mechanism whereby a large number of organizations agree to be covered under a single contract with a commercial insurance company.

Hard Market: Occurs during an ebb in the insurance industry cycle. A period when capacity in the insurance industry is too low to meet the demand for insurance. A hard market generally follows a time of declining interest rates. Prices for insurance are high during a hard market and in extreme situations, some types of insurance are completely unavailable.

Occurrence Policy: A type of insurance policy whereby the insurer agrees to provide protection if a claim is made after the term of a policy expires, as long as the liability occurred during the term of the policy. For example: A person slips and falls on an organization’s premises in November of 1986, but the incident is not reported to the insurance company until July of 1987. If the effective dates of the occurrence policy were from January 1986 to December 1986, the accident in November 1986 would be covered by that policy.

Reinsurance: Sometimes described as the insurance of insurance companies. It is essentially an insurance transaction whereby the reinsurer, for a premium, agrees to take on part or all of the risk accepted by the ceding company, that is, losses that may be sustained by the ceding insurance company. A major objective of reinsurance is to spread risk as broadly as possible to limit any individual insurance company’s liability arising out of large losses which it does not have the capacity to withstand.

Risk Pool (California): A mechanism whereby three or more (usually many) organizations share in providing protection against the risk of losses (liability only) of its individual members. The member organizations of the pool contribute capital and/or premiums to the pool. In general, these premiums are used to cover the administrative expenses of the pool and to pay claims. Membership in a pool authorized by AB 3445 is limited to California nonprofits.

Risk Retention Group: A risk-bearing entity which is created pursuant to the 1986 amendments to the Federal Risk Retention Act. The entity must be incorporated as an insurance company under the laws of one of the 50 states, must provide coverages (liability only) for the pre-designated membership group, and may operate in states other than its place of incorporation.

Risk Sharing: For the purposes of this paper, “risk sharing,” “risk pooling,” and “risk pool” in general refer to any of the three mechanisms available to nonprofits for sharing risks—a captive, a risk retention group, and a California risk pool. Risk sharing is a process whereby two or more (usually several) organizations agree to bear jointly the losses incurred by the member agencies. For all practical purposes, most of these mechanisms are insurance companies that are owned by the organizations they insure.

Soft Market: Occurs during a peak in the insurance industry cycle. A period when capacity and profitability in the insurance industry are high. During these times, insurers are usually competing for market share and prices for insurance premiums are low. Soft markets generally occur during periods of high interest rates.

Tort Reform: Some who believe that the current insurance crisis is a result of excessive jury verdicts and court awards support changes in the civil justice system, or tort reform. Generally proponents of such reform advocate placing dollar limits on court awards and/or limiting payments to attorneys. A more extensive list of proposed tort reforms appears in Appendix E.

B. Types of Liability Coverage

As stated earlier, the current “crisis” in the insurance industry is lodged primarily with property/casualty insurers and specifically with liability insurance. The following discussion describes the types of liability coverage often required by nonprofit organizations. [6]

General Liability: Most comprehensive general liability policies cover four types of costs:

- Bodily injury, which includes physical injury, pain and suffering, sickness and death;

- Damage to another’s property, including both destruction and loss of use;

- Immediate medical relief at the time of an accident;

- The legal cost of defending the organization in a lawsuit if the injured party decides to sue (the insurance company usually must pay the defense costs even if the suit is groundless or fraudulent).

General liability policies will likely not cover situations involving the following:

- Accidents where no one is at fault. For example, a client trips and falls but the accident did not result from any negligence on the part of the organization. (An accident insurance policy is usually required for these types of mishaps).

- Injuries to clients who are being transported by car, van or bus. Automobile insurance including coverage for bodily injury, property damage, and uninsured motorist protection is required for these types of claims.

- Physical or sexual abuse. In some civil cases, general liability coverage might pay for legal defense of an employee, but will not pay for any damages if the employee is found liable. General liability insurance will not cover costs if criminal charges are brought against an employee. Depending on the lawsuit and the insurance policy, an organization may or may not have coverage under a general liability policy if an employee is accused of physical or sexual abuse. Most general liability policies—especially for child care agencies—now specifically exclude child abuse provisions.

- Damage to your property. General liability insurance does not cover damage to your property, whether it is owned, rented or leased. Property insurance is written on a separate policy.

In addition to comprehensive general liability insurance, some or all of the following types of liability insurance may be useful for nonprofit organizations, depending on their specific needs.

Contractual liability: Sometimes this type of coverage is necessary to cover liabilities which are assumed under contracts, such as a lease which includes a clause whereby your organization agrees not to sue the landlord if an injury occurs on the premises.

Directors and officers liability: A general liability policy will protect board members and officers where the corporation is charged with negligence of the employees, but not if the board member or officers are separately sued for failing to make a prudent decision. In California, a director must (1) act in good faith; (2) in a manner the director believes to be in the best interest of the corporation; and (3) with such care, including reasonable inquiry, that an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances. Thus if a board of directors fails to have equipment repaired because of financial reasons, and someone is hurt by the equipment, the board members could be individually sued for failing to make a prudent decision.

Excess liability (or umbrella) coverage: An additional insurance policy to cover losses in excess of those covered by a general liability policy. For example, if the general liability policy covers losses up to $100,000, an excess policy might be purchased to cover losses over $100,000 and up to $500,000.

Fire legal liability: A general liability policy will not pay for any damage which occurs to the portion of a building which your organization occupies. If a renter causes a fire on the premises, the landlord’s insurance company may attempt to collect the cost of the repair from the renter. Fire liability insurance covers this type of cost.

Personal injury: While a general liability policy covers claims relating to bodily injury and property damage, personal injury liability coverage provides protection for a libel, slander, or an invasion of privacy lawsuit.

Products liability: If an organization serves food or has fundraising activities, such as bake sales, this type of insurance may be necessary. Sheltered workshops or other types of nonprofit organizations which actually produce a product that may be used by the public, such as toys or furniture, also require products liability insurance.

Professional errors and omissions: Often referred to as “malpractice insurance,” professional errors and omissions insurance may also be advisable for employees such as counselors or financial advisors. Premium prices for this type of coverage, and directors and officers coverage, if it can be found, are often ten to fifteen times larger than they were one year ago. Furthermore, coverage is subject to much lower maximum limits and the available policies have more exclusions such as reducing or eliminating coverage for publications, discrimination suits, employees, committee members and volunteers. It is likely going to be extremely difficult and/or expensive to obtain coverage for errors and omissions/directors and officers throughout 1987.

C. What to Look for in Liability Insurance Policies

The current “crisis” has initiated some important changes in the way liability insurance policies are being written. Most of these changes shift some of the risk previously carried by the insurer to the insured. It behooves the consumer to become educated about the nature of these changes. Important provisions to notice in a liability insurance policy include: [7]

Additional insureds: Funding sources and landlords sometimes require that they be named on your organization’s insurance policy. Sometimes employees and volunteers are also named as additional insureds. This means that if they are named as co-defendants in a suit against your organization, the insurance would cover both the cost of their defense and any part of the settlement or judgement against them.

Coverage: The time period covered by policies is changing. General liability policies before 1986 were usually “occurrence” also called “comprehensive” policies. The Insurance Services Organization developed a new form called “claims-made” or “commercial” which has been adopted by many insurers for general liability. These changes can significantly affect the extent of coverage provided.

During the years preceding the current crisis, policies were written under the “occurrence” form whereby the insurer agrees to provide protection if a claim is made after the term of a policy expires, if the liability occurred during the term of the policy. Sometimes this is changed to a “claims made” form, whereby both the occurrence and the claim of injury or loss must be reported to the insurance carrier within the effective dates of the policy.

Two provisions of the “claims-made” policy may leave the insured especially vulnerable. These are the ability of the insurer to change the “retroactive date” and a so called “laser” endorsement, which can be used to exclude losses after they have occurred. If a claim is made during the policy period for bodily injury or property damage that occurred before the “retroactive date” specified in that policy, the policy will not apply. Furthermore, at renewal, the insurer may move the “retroactive date” forward and leave the policy holder with a gap in coverage. The danger to the insured of the “laser” endorsement is that products, activities, or periods of time can be excluded after the premium has changed hands, and after losses have occurred.

An additional consequence of the “claims-made” policy is that organizations that change insurance carriers or go out of business must purchase “tail coverage” sometimes at rates 200 percent and more of the original coverage for each year they wish to protect themselves against lawsuits that might arise from earlier, unreported liabilities.

Definition of Loss: This statement describes the types of losses for which the insurance company is agreeing to pay. It is important to determine whether the loss provisions include legal fees and defense costs. Do not expect the insurance company to pay for fines and penalties imposed by law.

Limits of Liability: A prudent insurance consumer should notice both the limit of amount paid for each individual claim, as well as the aggregate amount paid for all claims. Even if the total premium cost has not increased, if the limits of coverage have been lowered the cost for each unit of insurance coverage has increased. These new limits may be inadequate to meet contract requirements of some funding sources.

Policy Exclusion: This section of a policy describes what activities this insurance policy will not cover. It is extremely important that a member of the organization consider each exclusion carefully to determine whether it represents an activity of the organization which could create liability. If one or more exclusions represent unacceptable risks to the organization, it may be necessary to purchase other insurance or to expand the present policy to remove the exclusion.

Retention or Deductible: Essentially the words retention or deductible when used in an insurance policy mean the same thing. A $2,000 retention or deductible per claim means that, on any claim, the organization will be required to pay the first $2,000. For example, on a $10,000 claim, the organization would pay $2,000 and the insurer $8,000. One way for an organization to lower its insurance costs is to increase the size of its retention. This should be done with full consideration of the assets available to the organization to pay the increased retention in case of a claim.

III. The Scope of the Problem

Faced with huge increases in liability insurance premiums in 1985 and 1986, nonprofit organizations have:

- Drastically cut services and staffs

- Been forced to use scarce reserves

- Raised fees

- Reduced insurance coverage

- In some cases closed completely

Nonprofit organizations have been especially hard hit by the liability insurance crisis because:

- They have relatively inflexible funding mechanisms which makes it difficult for them to pay for dramatic and unanticipated increases in the cost of doing business

- They often serve clients who cannot afford to pay price increases for services

- For some, the shortage of errors and omissions and directors and officers insurance has made it increasingly difficult to attract and retain trustees, officers, directors and volunteers

- Some programs such as child care, foster care, group homes, and health services frequently require liability insurance as a condition of licensure

- Some programs are required to have liability insurance to receive public funding

One study by United Way of Los Angeles found that a loan program to help nonprofits absorb the annual increase in insurance costs would require funds in excess of $2 million for the Los Angeles agencies alone. [8]

There are approximately 43,000 private nonprofit organizations in California. If one out of three of these organizations experienced a 50 percent increase in liability insurance premiums as a result of this crisis, extra out-of-pocket costs to the nonprofit sector over the two-year period 1985-86 could be estimated at approximately $32.3 million. [9]

However, if the insurance companies had limited increases to 50 percent on each policy, we might not have a “crisis” today. A study of United Way agencies in Illinois found that insurance premiums had increased by 223 percent over the 18-month period ending in May, 1986. [10] It was cancellations and premium increases like the following that strained many nonprofits’ ability to exist and brought the problem to crisis proportions. For example,

- A small-town development achievement center with no previous insurance claims saw its premium go from $891 to $22,000 [11]

- A program aiding the elderly with a community center and jobs program had its rate increased from $4,300 to $16,000 [12]

- A small theatre group had it rates increased from $750 to $12,000 for a policy that offered less coverage [13]

- The generally liability and medical malpractice of a women’s clinic was not renewed. Only when the clinic agreed to curtail all abortion services was coverage again offered. [14]

- A national survey in 1985 revealed that 20 percent of child care programs had had their insurance canceled or not renewed. [15]

A survey in early 1986 by the United Way of the Bay Area regarding nonprofit organizations and liability insurance revealed some striking results. Although technical flaws make it difficult to derive conclusions about the impact of the liability insurance crisis on nonprofits in California, the study shed considerable doubt on insurance industry claims that giant premium increases for the nonprofit sector are justified. [16]

IV. Causes of the “Crisis”: What Happened?

Confusion about the causes and scope of the liability insurance crisis is rampant. One association member put it this way, “[we] are being bombarded with facts and figures from several different coalitions and no one is quite sure who to believe, with which figures, about what issues.” [17] The crisis is commonly blamed on one or more of the following:

- The method of accounting used by the insurance industry

- The insurance industry practice of cash flow underwriting

- A changing civil justice system

A brief overview of each follows.

A. Industry accounting practice

To estimate future payouts prior to the date of actual payment, insurance companies consider primarily two factors; losses incurred but not reported, and loss development expense which may cause losses to grow over time because of inflation or other unforeseen changes. Insurance companies report the full amount of the sum of these estimated payments as an expense.

Critics of this practice point out that to pay out one dollar in the future, one needs to set aside much less than one dollar today because of the interest that dollar can earn in the interim. They argue that this practice of recording losses overstates payouts and makes industry profits seem lower than they actually are.

Changes in this particular accounting practice would put the property casualties industry’s total profit for 1985 at $7.4 billion, a net return of approximately 11 percent. [18] This is in contrast to reported industry earnings of $2 billion in 1985, or a 2.6 percent return on net worth. [19]

Insurance industry representatives argue that the current accounting practice already results in underreserving for future losses, and that a modification requiring discounting of future expenses would cause even more insurance company insolvencies. Any move to change this practice would meet with strong insurance industry resistance.

B. Cash Flow Underwriting

In 1981 the average interest rate on investments was approximately 18 percent. In 1985 it was 8 percent. For some, these figures alone explain the current liability crisis.

Insurance companies make money in two ways—premium collections that are higher than the losses they pay out and investment earnings from premium dollars. Higher interest rates mean that insurance companies make a higher return on the premium dollars they invest. As new companies enter the insurance market when investment earnings are high, competition increases and premium prices drop.

Problems occur when interest rates persistently decline and insurance companies do not incrementally increase premium prices to counteract lower investment gains. Extremely large price increases can result if insurers try in a short time to make up for several years of inadequate pricing and falling interest rates. [20]

Department of Insurance regulations require that insurers maintain a standard ratio of net written premiums to surplus funds available. Consequently, when premium prices go up, insurance companies must make increases in their available surplus funds that are proportionate to the premium increases, or write fewer policies until they are able to increase the amount of money they have in “surplus.” During the time that they are building up these surpluses, insurance companies which drastically increase premium prices cancel some policies and refuse to renew others. Those policies that are canceled or not renewed are often small accounts of those with risk exposure with which they were unfamiliar. Nonprofit organizations are feeling the impact of that practice.

A survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) in November 1985 found that nearly two-thirds of family day care homes, over one-third of child care centers, and over one-quarter of Head Start programs had not had their liability insurance renewed that year. This was despite the fact that over the past two years only six percent of the premiums they had paid to insurance companies had been paid out in claims.

C. The Changing Civil Justice System

Tort reform proponents mounted an enormous campaign to link the insurance crisis to problems with the civil justice system. The Insurance Information Institute spent a purported $6.5 million on television commercials in an attempt to convince the public of the need for tort reform. During 1985, 208 bills affecting tort law were enacted in 46 states. [21] Orio 51, which limits a defendant’s share of any pain-and-suffering award to the proportionate amount of the defendant’s degree of blame, was passed in California in 1986. The Wall Street Journal estimated that $12 million was spent on advertising and polling costs on that initiative, alone.

Proponents of tort reform generally acknowledge victims’ rights to be compensated for economic loss and repair of injury, but cite the following as proof that the civil justice system needs reform:

- The average size of a jury award has more than quadrupled over the last 25 years.

- Asbestos victims, who have sued to collect for costs incurred because of the effects of over-exposure to asbestos, received just 37 cents of each dollar and plaintiffs’ lawyers get 26 cents. [22]

- Insurers state that all legal related expenses for general liability lines have increased from 10 to 15 percent of all losses in 1967 to 36 percent in 1985. [23]

Opponents of tort reform claim that there is no causality between verdict trends and the insurance crisis. They argue that in the early 1980’s the same problems existed with the court system and yet insurance was available because interest rates were high. They claim that whether or not there is tort reform, there is still going to be an insurance availability crisis over the next couple of years. Reform opponents cite the following as evidence:

- Even though the average size of a jury award has increased, the increases are not from the type of cases which are said to underlie the current insurance crisis—negligence, product liability, miscellaneous personal injury, and professional malpractice cases. [24]

- The average jury award in San Francisco doubled during the first half of the 1970’s and remained constant during the second half of the decade. In 1979 the total sum of money awarded by all civil juries in San Francisco, in real terms, was only slightly larger than that in the early 1960’s. [25]

- Extensive tort reforms were enacted in Ontario, Canada during the 1970’s. Despite this fact, many organizations, including most daycare centers and nearly every Canadian School Board in that province were again unable to obtain liability coverage in 1985. [26]

- A report by the League of California Cities, in which 357 of the 441 cities polled responded, found that the amount of money paid in joint and several liability cases had decreased from $18.4 million in 1982-83 to $16.9 million in 1984-85, and the number of cities involved in both judgements and settlements decreased by 20 percent over the same three-year period.

- In the 1970’s insurers warned that there would be no more municipal liability coverage without tort reform. Critics recall that the latter never happened and the former reappeared. In time, they presume, that will happen again. [27]

- Long term trends towards more tort lawsuits, toward increased liability for damages, and toward larger verdicts for the most seriously injured plaintiffs have been well-established for decades. However, there is no clear evidence that the trends have accelerated in recent years or that the sharp increases in insurance premiums and crisis in availability have been caused by any recent change in those trends. [28]

It is likely that all three of these causes for the crisis listed above—industry accounting practices, cash flow underwriting, and the civil justice system—contributed to the higher liability insurance prices in 1985 and 1986 with cash flow underwriting contributing the largest share. Whatever the causes, however, there currently exists a shortage of capacity to write liability insurance. As is generally the case when something is in short supply, prices are high and sometimes the product is at least temporarily unavailable. The following section examines the options available to nonprofits for improving their position within the commercial insurance market.

V. Private Nonprofits: Why Are They Vulnerable? What Can They Do?

Nonprofits are hard hit during insurance industry cycle ebbs when profitability is low not because they are inherently more risky than comparable for-profit operations, but because the services provided by nonprofits are generally not well understood by insurers. The best evidence available for illustrating that nonprofits are not higher risks, but are poorly understood by most commercial insurers is provided by those in the insurance business who also are familiar with nonprofits.

In Illinois there exist insurance mechanisms called pools which insure only charitable nonprofit organizations. If nonprofits had, indeed, become more risky in recent years, these pools would be refusing to renew policies and/or dramatically increasing prices like other commercial insurers. To the contrary, instead of limiting or denying coverage to nonprofit organizations, these risk pools for nonprofits in Illinois have doubled the insurance they write during the past few years.

Many insurance companies use the services of Insurance Services Organization (ISO). This organization collects data from member insurance companies in order to help them estimate the proper rates to charge. Many categories of nonprofit organizations, however, are not classified separately by ISO. Furthermore, ISO itself admits that its data is flawed and cannot be used to adequately assess fair rates even for many of the categories of risk on which it keeps data. In California, the Department of Insurance concurs in this conclusion. [29]

This means that the largest information source available for estimating risk and setting rates is not helpful for judging the risk characteristics of many segments of the nonprofit sector. In a later section of this paper, advocating better reporting of insurance industry data is offered as one way in which nonprofits might seek to improve their position within the commercial insurance industry.

Nonprofit organizations generally fill areas of specialized need and tailor services to the specific needs of those in their particular locality. Unless they specialize in underwriting nonprofit insurance coverage, it is often difficult for insurance underwriters, unfamiliar with the nonprofit sector, to evaluate the risks of these many specialized services.

The modest premium dollars to be gained from insuring often small nonprofit organizations offer little incentive for insurance companies to undergo the costly process of collecting information about risk exposure which is necessary to accurately estimate fair premium prices.

As discussed later in this paper, creating a risk sharing mechanism for California nonprofits offers one way of collecting a large body of information about the risk exposure and loss history of the nonprofit sector and might provide useful information that is not currently available for California.

A. Potential Solutions Not Involving Risk Sharing

The nonprofit sector can circumvent, or at least try to moderate their disadvantageous position within the insurance marketplace in three ways:

- Pure self-insurance (“going bare”)

- Seek government intervention into the market

- Purchase insurance in groups

1. Pure self-insurance (“going bare”)

On its face, the option to purchase no liability insurance (i.e. self-insure) might be appealing for those nonprofits who are not required by law or funding sources to do so. Recent legislation was passed in California (SB 2154, see Appendix A) to clarify the responsibilities of directors of nonprofit organizations. In California, a director must (1) act in good faith; (2) in a manner the director believes to be in the best interest of the corporation; and (3) with such care, including reasonable inquiry, that an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances.

It is not clear, however, that a court would agree that by deciding not to purchase liability insurance that a director was convinced that he or she was acting in the best interest of the nonprofit corporation and that an “ordinarily prudent person” would do likewise. Therefore, a board of directors which authorizes a nonprofit organization to operate without general liability insurance might think twice about whether that is a prudent decision.

Agency management considering whether or not to purchase insurance must evaluate the ability of the agency to conduct prudent risk management and limit claims in light of the resources available to the agency to pay potentially high losses. A major weakness of self-insurance is that even if a large reserve of cash is set aside to administer claims, pay the required legal fees, and pay the award for claims, the organization might still find itself with insufficient funds to cover one or more unexpectedly large claims. In that case, not only might the organization be forced to close, but its directors and officers might be liable for an imprudent decision.

2. Government Intervention

Two alternatives often suggested as government solutions to the liability insurance problems of nonprofits are Market Assistance Programs (MAP) and Joint Underwriting Authorities (JUA).

A Market Assistance Program is a voluntary organization of insurance companies which agree to examine applications of organizations and to offer policies to some of those who have been denied coverage on the voluntary market. MAPs can sometimes help to make insurance more available by providing a centralized mechanism for submission of applications. Unfortunately, MAPs do little to make insurance more affordable during insurance industry cycle ebbs.

The Cal Care Market Assistance Program was created in October of 1985 for daycare providers in California. Approximately 30 insurance companies participate in the plan. Originally Cal Care was expected to process between 4,000 and 5,000 applications by the spring of 1986. By mid-summer only about 100 policies were written as a result of this program. Daycare providers complain that Cal Care is too slow to offer them practical help. Furthermore, the lowest rate of any of the participating companies is $50 per child per day, seven times the 1984 rate.

With SB 1590 the California legislature in 1986 authorized the Insurance Commissioner to allow the formation of a MAP for liability insurance for classes of risk for which liability insurance is not readily available. There is no evidence, however, to indicate that a MAP created for nonprofits would be any more successful than Cal Care. A few more nonprofits might be able to locate an insurance company willing to provide insurance, but the process is likely to be as slow and expensive as the childcare experience. Furthermore, if a MAP were created for nonprofits it might be wrongly assumed that their insurance problems are solved and deflect the creation of a more useful solutions.

A Joint Underwriting Authority is a legislatively authorized body, organized through the State Department of Insurance, whereby insurers are obligated to write insurance for organizations which cannot find insurance in the market. Unlike a MAP, participation by insurance companies is not voluntary.

JUAs are, therefore, a mechanism whereby the government mandates that the commercial market insure high risks at prices lower than the expected costs. JUAs are typically created for sectors that have an especially high exposure to risk, and are mechanisms whereby the costs of these risks are subsidized by others in the market. Creating such a mechanism to provide liability insurance for nonprofits, would be tantamount to admitting that the nonprofit sector is inherently more risky.

Because it is a government mandated solution, a JUA for nonprofits would be strongly opposed by the insurance industry. In 1986, nonprofit organizations in Massachusetts lobbied for the creation of a JUA, but it was defeated because of industry opposition. Typical of most JUAs, the Massachusetts JUA would have forced all insurance companies to write liability insurance for human service agencies or forfeit their right to offer any insurance anywhere in the state. A voluntary MAP was created instead and it is too early to determine whether it will be of assistance to the nonprofit community in Massachusetts. Whether or not it makes liability insurance more available, it is not expected to lower premium prices. [30]

Like MAPS, JUAs do not increase insurance industry capacity which is low because of a temporarily low profitability in the insurance industry. Consequently, JUAs can at best only slightly increase insurance availability. During an ebb in the insurance industry cycle such as is being experienced during the mid-1980’s, JUAs will not necessarily make insurance more affordable.

Two pieces of legislation were introduced in the California Assembly in 1986 to form JUAs. AB 3281 was to provide a JUA for liability insurance coverage for birthing personnel and facilities which were unable to obtain insurance through ordinary methods. This bill was stalled in committee. Another bill AB 2162 would have created first a MAP and then, if necessary, a JUA for liability insurance. That bill was defeated. Seeking the creation of a JUA for nonprofits would require extensive resources and prospects for success are not good.

3. Group purchasing

A group insurance plan is a mechanism whereby a large number of organizations agree to be covered under a single contract with a commercial insurance company. Sometimes this strategy can help smaller organizations compete with larger firms for limited insurance capacity by providing insurance companies a larger share of the nonprofit market with fewer administrative costs. The following describe the potential benefits from group insurance: [31]

- Greater availability. If the group is underwritten as a group and not on an individual basis, some members of the group that are inherently more risky may be covered that otherwise would not be able to be insured—at least at that price. All organizations pay a proportion of the average risk for the group.

- More favorable rates. If the insurer spends less money on administrative expenses, more money is available to pay losses. In the mid-1980’s market, however, group participants are not likely to find premiums significantly lower than the market rate for non-group members.

- Tailor made coverage. Individual organizations in the commercial insurance market are generally forced to take insurance coverage provisions written into standardized forms. A large enough group may be able to negotiate coverage tailored to the specific needs of its type of organization. Although this may also enable groups to insure for additional perils not usually covered by standard forms, it is not a likely vehicle for providing directors and officers insurance, at least in the current tight market.

- Risk management. A large group of similar agencies which has a contract with an insurer for a group policy might also have the risk management services of that insurer available to its members.

- Premiums based on net cost. A very large group can sometimes negotiate premium payment on a net cost basis whereby some of the excess premiums are refunded to the members of the group at year end. Insurers, however, generally do not offer these types of arrangements during cycle ebbs when profitability is low. As illustrated in a later section of this paper, if a group is large enough to extract this kind of arrangement from an insurer, a risk sharing mechanism may be an even better option than a group because risk sharing has the additional benefit of providing more stable capacity during insurance industry cycle ebbs.

Group plans are currently one method being used to make liability coverage more available to day care providers. The policies generally have stringent eligibility requirements such as those specifying that a center must have a minimum enrollment, operate for a certain number of hours per week, and receive limited government support. Despite the restrictive nature of these groups, the premium prices still are considered to be high. The average cost per child was $7 per year for day care centers in 1984, Averages with some of these group policies now range between $50 and $70 per child per year. Some groups also require that the entire years’ premium be paid in advance. [32]

One group of 60 nonprofits in southern California is working to organize a group liability policy. Group members will be refunded a portion of their premium based on administrative cost savings, however, rates are not expected to be significantly lower than the current market rate. [33]

Half of the nation’s 2,800 nurse-midwives had such a group policy which was canceled abruptly in May of 1985, even though only three percent of nurse-midwives (in contrast to 70 percent of obstetricians) have been sued for malpractice. The insurer, with less capacity to write insurance during the current crisis, dropped those accounts it believed represented high or unpredictable risks. [34]

Group purchasing, while potentially a useful short-run strategy for increasing the availability of liability insurance for nonprofit organizations, provides no assurance that the group members will not be dropped when an insurer needs to diminish the amount of insurance it writes during times of lower profitability. Despite its limitations, group purchasing might become more common in the future because of recent amendments to the federal Risk Retention Act which make it easier for insurance companies to offer group policies. Furthermore, group purchasing is less costly and less difficult than the risk sharing alternatives described in the following section and may prove to be a useful alternative for some nonprofits.

Nonprofits groups which are interested in forming a purchase group for liability insurance can learn more about the applicability to their needs of this alternative by contacting a broker or insurance consulting firm. Touche-Ross is currently working to organize a group for the Center for Nonprofit Management in Los Angeles and may be able to provide information to other interested groups.

Table 1 summarizes the various alternatives other than risk sharing mechanisms available to nonprofits for addressing the liability insurance crisis. A discussion of risk sharing alternatives follows.

| TABLE 1. Summary of Alternatives other than Risk Sharing | ||

|---|---|---|

| ALTERNATIVE | STRENGTHS | LIMITATIONS |

| Self-insure (“go bare”) | • Circumvents problems with cost and availability | • Insurance is required by some funding sources • Board members might be held liable • Substantial financial reserves required |

| Market Assistance Program | • Sometimes increases availability | • Slow process • Questionable effectiveness • Does not help decrease price in a hard market |

| Joint Underwriting Authority | • Increases availability | • Generally opposed by insurance industry • Mechanism for subsidizing high risk and not suited to needs of nonprofit sector • Unlikely to decrease price in a hard market |

| Group Purchasing | • May increase availability • Potential for tailormade policies • Might slightly decrease price | • In hard market groups vulnerable to same extreme price increases and cancellations as individuals |

B. Potential Solutions Involving Risk Sharing

The nonprofit sector in California has three alternatives for expanding the commercial insurance market to help make insurance more available and affordable. These are:

- Captive insurance company

- Risk retention group

- Risk pool

Each of the three alternatives listed above are mechanisms whereby nonprofit organizations can join their resources and, in effect, own their own insurance company and spread the risk of liability losses by sharing the risk across a large number of organizations. The legal and organizational differences among these three mechanisms are described briefly below to give the reader some sense of the technicalities that separate them as alternatives.

1. Captive insurance company

A “captive”, sometimes referred to as an “offshore”, is an insurance company that is solely owned by those entities it insures. Members capitalize the captive and pay premiums to the captive which are used to pay losses and administrative costs. Profits are either retained by the captive to create surpluses or are returned to the insureds (owners) in the form of dividends or reduce premiums.

During the last cycle ebb in the insurance market during the mid-1970’s, malpractice insurance became scarce and extremely expensive. Doctors formed their own captive insurance companies which have introduced a somewhat stable supply of medical malpractice insurance and have been instrumental in limiting premium increases. [35] Many of the medical malpractice captives, were organized “offshore”, in the Cayman Islands and Bermuda, to avoid United States tax obligations and to escape the requirements of the California Insurance Commissioner.

One of the costs of operating an offshore captive is the need to secure the services of a “fronting” company, another primary insurance company that is licensed to write insurance in the state. Fronting costs alone can be as much as 12 to 19 percent of premiums.

2. Risk Retention Group

A risk retention group is essentially a captive insurance company that is organized under the recent provisions of the amendments to the federal Risk Retention Act (see Appendix B) which authorizes the creation of risk retention groups beginning in January of 1987. A risk retention group differs from a captive in the following ways:

- A risk retention group is prohibited by law from offering any insurance other than liability insurance.

- Each state requires that insurers organized in that state be part of a mechanism called a “guaranty fund” which protects policyholders in case an insurance company becomes insolvent. A risk retention group is prohibited by law from participating in any state guaranty fund. Risk retention groups were excluded from participation in any guaranty fund because of insurance industry pressure. Some believe that their inability to be participants in such a fund will make risk retention groups less attractive. Others argue that a guaranty fund is seldom used that the inability to participate is not a handicap.

- A risk retention group, while required to be licensed as an insurance company, is not regulated by the state Insurance Commission.

3. Risk Pool

In 1986, the California legislature passed AB 3545 (see Appendix C) which authorizes nonprofit organizations in California to create risk pools. Similar to a captive and a risk retention group, a risk pool is also a mechanism whereby three or more (usually many) organizations share in securing protection against the risk of losses. The member organizations of the pool contribute premiums and sometimes capital funds to the pool. Premiums are used to cover the administrative expenses of the pool and to pay claims. Like a risk retention group, a California risk pool has the following characteristics:

- It is not subject to regulation by the Insurance Commission

- It is not able to be part of the state guaranty fund.

- It can pool risk only for tort liability losses. This includes third party liability such as general liability, directors and officers, and errors and omissions. It does not include property coverage for fire or theft.

Unlike a captive and a risk retention group, a California risk pool has these special characteristics:

- Membership in the pool is limited to California nonprofits.

- A pool need not be licenses as an insurance company.

The primary differences among a captive, a risk retention group, and a California risk pool are outlined in Table 2.

Which alternative is best?

A quick glance at Table 2 might lead the reader to conclude that a captive insurance company is obviously the best alternative. However, the requirements for establishing and administering a captive insurance company are stricter and more expensive than either a risk retention group or a California risk pool. Other, sometimes complex, tradeoffs must be considered when choosing the best alternative.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to determine which of these three alternatives is the best option for the nonprofit sector to pursue. More specific information that can be obtained only through an in-depth and technical feasibility study is required before such a determination can be made. Questions about the composition of the proposed membership, their risk exposures, the members’ primary insurance needs, the commitment of the members, and the money available for capitalization must be answered before the best alternative can be determined. A better understanding of the concept of risk sharing in general, however, can enable nonprofit management to weigh the relative merits of each alternative.

The following section describes the benefits of and problems with the risk sharing concept in general, whether the mechanism is a captive insurance company, a risk retention group, or a risk pool. Unless otherwise noted, the terms “risk sharing”, “risk pooling”, and “risk pool” refer to any of the three alternatives. When significant differences exist among the alternatives, those differences are specifically noted by the terms “captive,” “risk retention group,” or “California pool.”

VI. Risk Sharing: The Most Powerful Tool Available To Nonprofits

Many municipalities have chosen the risk pooling option. Business Insurance reports that the number of municipal risk pools has increased to more than 200 nationwide. [36] The National League of Cities reports that membership in some existing pools quadrupled in 1986. It is estimated that 60 percent of public entities will belong to some form of risk pooling program within the next five to 10 years. [37] Self-insurance, captive insurance companies and pools accounted for just 12 percent of the commercial property/casualty business in 1975, but by 1985 the figure had grown to 25 percent. [38]

A. Existing Nonprofit Risk Sharing Mechanism

In 1979 Illinois passed legislation making it possible for nonprofit organizations in that state to create risk sharing mechanisms (also called risk pools or risk pooling). Two organizations in Illinois now operate risk sharing mechanisms for nonprofit organizations. The Christian Brothers Religious and Charitable Risk Pooling Trust Program in Romeoville has insured charitable Catholic organizations in several states since 1980. First Non Profit Risk Pooling Trust, in Chicago, a risk pool strictly for Illinois nonprofits, has provided liability and property coverage for all types of nonprofit charitable organizations 1979.

Although the legislation authorizing these Illinois risk pools is somewhat different from that authorizing the various risk sharing mechanisms in California and other states, these Illinois pools are similar enough to the type of mechanism that could be organized elsewhere to allow a close comparison.

During the past few years, when other commercial insurers have canceled and not renewed liability policies for nonprofits, these two risk pools have more than doubled the number of policies they write for nonprofits. These pools had good information about the risk exposure of nonprofits before the current crisis and continued throughout 1985 and 1986 to write new policies for nonprofits as they had in previous years. These risk pools did not share in the insurance industry fears, stemming from inadequate data and a few sensational news stories, that day care or counseling centers or performing arts had suddenly become exceedingly risky. These risk pools had reliable data from which to estimate fair premiums.

The success of these two risk pools provide strong evidence that similar risk pools could operate successfully in California and in other states and exert some control over insurance coverage and prices. The experiences of these pools, as described below, also show that risk pools are not immune from insurance industry cycles, and their experiences underscore the importance of prudent management and underwriting practices if risk pools are to be able to moderate the impacts of insurance industry cycles.

1. Christian Brothers Religious and Charitable Risk Pooling Trust Program

The Christian Brothers Trust (CBT) started in Illinois in 1955 as a group purchasing program with insured property values of $13,000,000, including 42 automobiles. In 1980 the CBT was reorganized as a risk pool under the Illinois legislation and provides all types of liability and property coverage for Catholic nonprofits. The pool in 1984 insured $1.4 billion in property values, including 4800 vehicles. It currently has 2,500 participating Catholic organizations in 47 states. Before the new amendments to the Risk Retention Act, pooling with organizations in other states was technically illegal. The CBT has ignored this technicality since its inception. [39]

This pool raised prices for general liability by 170 percent during 1985 and yet was able to increase its membership during that time by 45 percent. The reasons given by the Christian Brothers Trust management for the sharp increases are not increases in payouts to courts and in legal fees.

They are:

- Insurance companies and risk pools usually purchase insurance for large losses from other commercial insurance companies. The commercial insurers that were selling this excess insurance (or reinsurance) to the CBT placed severe exclusions on CBT about the types of insurance coverage the CBT could provide. For example, the reinsurers excluded child abuse as an insurable event. Instead of decreasing coverage to nonprofits or dropping individual organizations, the CBT chose to self-insure and to do so hard to raise premiums.

- A decision by management to stop offering rates that were subsidized by the Catholic Church. In essence the Trust raised rates in 1985 to compensate for several years of inadequate rates.

Members stayed with the Christian Brothers Trust and new members joined in spite of the increase because:

- The CBT continued to offer a wide range of coverage—including coverage for child abuse, directors and officers, and errors and omissions. They did not reduce types and limits of coverage.

- Even with the large increases, the prices offered by the Christian Brothers Trust were 25 to 30 percent below rates offered by commercial insurers.

The Christian Brothers Trust experience underscores the importance of management decisions in allowing a risk pool to maintain stable prices. If a risk pool engages in the practice of cash flow underwriting, as described in an earlier section, or for some other reason charges premiums that are inadequate for the amount of risk being underwritten, eventually they may be forced to drastically raise their prices as the CBT did in 1985. No pool could consistently undercut commercial prices and expect to maintain stable prices.

2. First Non Profit Risk Pooling Trust

First Nonprofit Risk Pooling Trust (First Trust) started in 1979 in response to the last insurance crisis in the mid-1970’s. At that time, the insurance industry had entered the longest and most price competitive “soft” market cycle in its history. In this competitive atmosphere, with prices for commercial insurance low, First Trust had a very difficult time getting started.

It started with a capital base of only $75,000. By the end of its first year, it had only 67 members. By 1980 First Trust had grown to 123 members, and by 1984 it was serving 714 charitable organizations. In contrast to most commercial insurers, First Trust greatly expanded it services to the nonprofit sector in 1985. During that year it increased its number of participants to 1000, a 35 percent increase over 1984. In 1986 it has grown to serving almost 1400 organizations. It has 487 members in its Illinois pool and is helping to insure 889 nonprofit organizations in other states through a type of broker arrangement. First Trust currently offers all types of property/casualty coverage, including directors and officers liability and property coverage for fire and theft.

Unless it reorganizes as a risk retention group, First Trust cannot allow nonprofits in other states to join its pool. It currently assists nonprofits in other states only by acting as a liaison with commercial insurers. Because First Trust is valued for its experience underwriting nonprofit organizations, Great American, an insurance company in California has engaged the services of First Trust to help evaluate California nonprofits who wish to be insured by Great American. Unfortunately, the underwriting guidelines in place by Great American are stricter than those used by First Trust to admit members to their Illinois pool. Consequently, many California nonprofits have been refused coverage by the Great American program.

In order to expand its coverage to as many Illinois nonprofits as possible and generate income to pay for anticipated increases in its own insurance (reinsurance), First Trust increased rates as much as 52 percent in 1985. First Trust, however, was able to avoid the huge increases and nonrenewals imposed by other insurers. First Trust’s 1980 Annual Report contained the following promise and prediction:

First Trust has gone about structuring its programs so that it will remain detached from the industry’s cycle. The result will be that First Trust will still be offering low cost, comprehensive benefits when the traditional insurance market is withdrawing into the sanctuary of selectivity, conservatism, and expensiveness.

In 1986 First Trust’s chairman commented, “Four years later [starting in 1984], both First Trust and the industry fulfilled their predicted roles.”

The chairman is making the point that First Trust did not engage in cash flow underwriting by pricing below actuarially sound standards in order to increase the amount of insurance it wrote. Instead it consistently wrote policies at prices which allowed it to maintain stable capacity. When others in the industry were experiencing the cycle ebb and dropping risks with which they were unfamiliar, First Trust was in a position to help nonprofits. During the recent crisis First Trust doubled the number of policies it wrote for the nonprofit sector while maintaining comprehensive coverage and reasonable prices.

B. Difference Between Illinois Pools and Available Alternatives

Organized as a California pool or a risk retention group, a risk pool would differ from the Illinois pools in two ways:

- A California pool or risk retention group can share risk only for liability losses such as general liability, directors and officers, errors and omissions and auto liability. Unlike the Illinois pools, a California pool or risk retention group could not insure against fire or crime losses.

- A California pool or risk retention group, unlike the Illinois pools, would not be regulated by the Insurance Commission.

Some suggest that nonprofit risk pooling in California may be more difficult than in Illinois because:

- Large settlements tend to be even larger in California than in Illinois. However, these large settlements appear to be due to “high-stakes” cases which are nearly all in intentional tort or in contract/business and would not be expected to be associated with nonprofit organizations.

- California nonprofit management may be somewhat more “entrepreneurial” than in Illinois. Thus, members might be less willing to commit to membership in a pool and more inclined to leave the pool to seek lower commercial rates during “soft” parts of the industry cycle. If large numbers of the membership left the pool during these times, the stability of the pool would be in jeopardy and the pool would likely not be available to help nonprofits when commercial prices again increase and policies are not renewed during another cycle ebb in the insurance industry.

Nonprofit risk pooling may be easier in California than in Illinois because:

- The “entrepreneurial” spirit and management flexibility in California might help the pool get started. Nonprofit management in California might be less hesitant than their Illinois counterparts were at first to become part of an innovative insurance alternative.

- Auto statistics are very good in California. This would allow a risk pool to accurately predict and write auto liability insurance policies.

- The number of potential participants in a risk pool is much larger than in Illinois. California has about four times as many nonprofit organizations as does Illinois.

C. Potential Benefits of Risk Sharing

The risk pooling option in general offers several potential benefits to the nonprofit sector over commercial insurance:

- Organized as a nonprofit, a pool can offer prices that, on average, are lower than those offered by commercial insurers. Lower prices may be possible because better information about the nonprofit sector allows the pools to charge a price that reflects the calculated risk cost. They do not need to include in the premium price a large “fudge factor” for risks with which they are unfamiliar. (For estimates of premium dollars that might be saved by a risk sharing mechanism for California nonprofits, see Appendix D.)

- Pool members might be able to have access to the pool with or without the services of a broker. Having this option would allow more flexibility, especially to large nonprofits which might already possess the inhouse expertise to arrange insurance coverage. First Trust in Illinois offers this option, however, some insurance consultants suggest that this type of arrangement might not be advisable for a risk sharing mechanism at this time. [40]

- Stable prices. A pool’s premiums would necessarily reflect trends in judicial awards, but conservative underwriting practice coupled with sound business management should enable a pool to maintain premiums at a relatively stable level.

- Additional stable capacity. During the current crisis, nonprofits faced both extreme price increases and policy cancellations. A conservatively managed pool would not have profit motivation to undercut underwriting realities during periods of high interest rates and would not be forced to drop smaller clients when interest rates fall.

- Policies and coverage tailor made for the nonprofit sector. A pool could be organized such that participants are represented through an elected Board of Trustees which could work with the pool’s administration and underwriters to help establish policies that reflect the insurance needs of the nonprofit community.

- Risk management by those who specialize in the nonprofit field. Management of existing nonprofit risk pools report that members of nonprofit organizations are generally eager to take steps to reduce the risks to which their employees and clients are exposed.

- Ability to establish a rating structure based on past risk experience. Over time, a risk pool would be able to gather extensive information, not currently available, about the risk exposures of nonprofits in California. During the current crisis the nonprofit sector has been at a disadvantage by having inadequate information with which address insurance industry charges that many nonprofits are too risky to insure.

- Moderating force for commercial insurers of nonprofits. At first, a pool would be too small to have much impact on other commercial insurers of nonprofits. As the pool grew, however, it might act as a check on extreme price increases during hard markets.

D. Limitations of Risk Sharing Mechanisms

Some of the policies that would help a risk pool become a stable source of liability coverage for nonprofits might also make the pool seem rigid and inefficient.

- At first, a risk sharing mechanism might be criticized for being overly selective. This does not infer that a pool would only select the lowest possible risks or that it would be expected to exclude organizations because of potentially high risks. Rather, the composition of a pool would need to be balanced, and risks chosen prudently, especially at first to protect the modest capital base of a new pool. In addition, the pool would need to purchase excess insurance or reinsurance to provide protection from large losses. Both of these actions would require the rejection of some pool applicants and would be unpopular with some members of the nonprofit community.

The factors that determine what risk would be acceptable are not necessarily based on the amount of the risk but rather on the composition of the risks of the total pool and how they interact. The criteria change with, among other things, capacity changes in the reinsurance market. In general, the higher rate of initial capitalization, the more the decision about acceptable risks rests with the pool management and not with the reinsuring company. - A risk pool that continued conservative underwriting practices when others in the commercial liability insurance market were competing for market share might not be able to offer competitive premiums during “soft” markets. This is not a flaw in the pooling structure, nor does it necessarily imply that the risk pooling mechanism is inefficient. To choose not to engage in cash flow underwriting is to choose to have stable capacity and stable premium prices during market cycle ebbs instead of short-term price gains during times of higher investment earnings.

- A risk sharing mechanism might require a commitment over time from its members. Part of the success of a nonprofit risk pool would depend on its ability to retain members during times when the commercial market may offer temptingly lower prices. There are trade-offs between having stable capacity and prices and enduring times when pool prices might sometimes be higher than the commercial market.

- A California pool and a risk retention group cannot participate in the state guaranty fund. In case of insolvency, these risk sharing mechanisms would not be covered by this fund. The management of First Trust listed this as one of the major difficulties they had initially in trying to market First Trust to Illinois nonprofits. This difficulty was overcome by developing a good reputation for responsible management and by demonstrating First Trust’s ability to consistently provide stable and affordable insurance for the nonprofit sector.

Table 3 below outlines the potential benefits and limitations of risk sharing mechanisms.

| TABLE 3. Summary of Potential Benefits and Limitations of Risk Sharing Mechanisms | |

|---|---|

| BENEFITS | LIMITATIONS |

| • Potentially lower average prices • Relatively stable prices • Stable capacity • Policies and coverage tailormade for nonprofit sector • Risk management by specialists in nonprofit field • Rates based on risk experience • Potential to moderate commercial market price swings | • At first might be criticized for selectivity • Prices might be higher than commercial prices during soft markets • Might require commitment of time from members • Unless organized as a captive, cannot be part of the state guaranty fund |

E. Potential Implementation Barriers

Most risk pools purchase reinsurance (which is insurance for insurers) and consequently do not operate separately from the commercial insurance market. Without a cushion of reinsurance (sometimes called excess insurance), a risk pool might put the assets of its members at risk to help fund large claims.

The current capacity shortage in the reinsurance market might affect the price and types of reinsurance available to a risk sharing mechanism in the following ways:

- Higher capital requirements. Because of stricter underwriting standards that accompany a capacity shortage in the reinsurance market, the $250,000 required by AB 3545 will likely be too little to convince reinsurers to provide excess coverage for a California risk pool. Estimates of the capital required to start a risk pool in California range from $350,000 to $2 million.

- Restrictions on pool membership. Reinsurers might be reluctant offer coverage for certain types of programs, such as residential and medical facilities. Pool management would have to be prudent in its selection of risks and might be expected to reject 10 to 15 percent of its applicants. However, summarily excluding all of the risks of broad classes of organizations would limit the effectiveness of a pool and make it unpopular with some in the nonprofit sector.

F. Prospects for Success

The best evidence currently available to predict the potential success of a liability risk pool for nonprofits is the success of existing nonprofit pools in other states. Those in the best position to know about the risk exposure of nonprofits, existing nonprofit risk pools, have doubled the amount of insurance they write for nonprofits during the past several years.

As the Illinois experience has shown, the ability of a risk pool to help the nonprofit sector is limited by the amount of available capital and by the pool’s ability to buffer swings in the reinsurance market. Nonprofits in Illinois report that the true measure of the success of their risk pools during this recent crisis is that these pools did not reduce coverage or cancel policies. [41]

Preliminary discussions with experts who are experienced in the field of nonprofit insurance indicate that a strong pool could be composed of private nonprofit organizations in California and could be expected to achieve the stability and success of similar pools currently operating in other states. [42]

1987 would be a particularly favorable year to begin a liability risk pool because:

- During the current hard market commercial liability premium prices are especially high to make up for investment losses. If the hard market is sustained throughout 1987, and commercial insurers continue to charge high prices aimed at replacing lost surpluses, a risk pool, even though somewhat hampered by high reinsurance rates, could offer favorable rates.

- Having faced high premium rates and canceled or reduced coverage for the past 18 months, nonprofits are currently painfully aware of their vulnerability in the insurance marketplace. Recently educated about the state of the commercial insurance market, nonprofit managers are currently in a good position to understand the benefits of risk sharing and be more willing to try a new alternative that promises to provide a stable source of insurance coverage.

Growth of a risk sharing mechanism might be slow at first if:

- The insurance market improves sooner than expected and commercial insurance prices decline rapidly during 1987.

- Nonprofit organizations, which after much searching during 1985 and 1986 have finally found coverage in the commercial market, are unwilling to put additional effort into charging their insurance coverage over to a risk sharing mechanism.